In February 2012, a 17-year-old Black boy was shot dead in the streets of Florida by a neighbor who felt this boy looked suspicious. Carrying a can of iced tea and a bag of Skittles, Trayvon Martin became yet another name added to the list of Black lives lost to racism. What surely shattered all hope, was that even after the facts of the case were reviewed, his killer was let free by the criminal justice system.

In February 2012, a 17-year-old Black boy was shot dead in the streets of Florida by a neighbor who felt this boy looked suspicious. Carrying a can of iced tea and a bag of Skittles, Trayvon Martin became yet another name added to the list of Black lives lost to racism. What surely shattered all hope, was that even after the facts of the case were reviewed, his killer was let free by the criminal justice system.

For Black youth in America, Trayvon Martin’s death opened up a new side to the world we all occupied. Trayvon’s death opened the door to all the lessons our parents had warned us about, all the side-eyes and stern looks your parents gave you to behave in public: keep your hands out of your pockets, and don’t give people a reason to think less of you. His death was a reminder that no matter how well we behaved or how well we performed—we would always be Black first.

After Trayvon came Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray and too many more. Their names and their deaths make up the rhythmic heartbeat of too many Black people in America—this ode is as real and as constant as the day-to-day lives of Black people in the U.S and abroad.

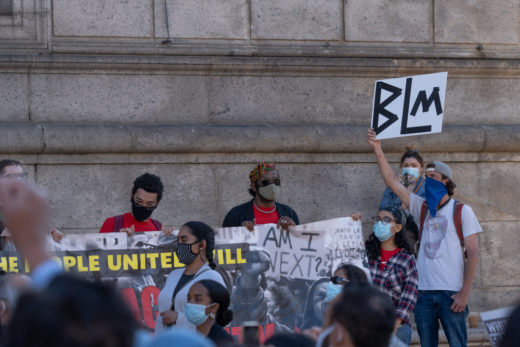

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement was started in 2013 by three Black women who were sick and tired of all the lives lost. They created this movement in response to the acquittal of the man who shot and killed Trayvon Martin. Since its inception, BLM has gone worldwide, a cross-continental connection of people standing in support of Black life through national protests, marches and other actions calling out racial injustice and police brutality against Black and brown people.

Today, with the use of social media such as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and more, not a moment goes by when young people are not connected. From this movement comes the emergence of the online voices of Black students at Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs).

The BLM movement leads to @Blackat___

Student voice has always been an instrumental part of any call for change … from the 1964 Civil Rights Movement and antiwar protests to student mobilizing around police violence against Black bodies in 2012 and on. Whether through student-led marches, sit-ins, protest or vigils, students have always had the physical on-campus space to confront and advance issues of diversity, equity and inclusion within their institutions. The past year has been a transformative one because, despite society being on lockdown due to COVID-19, students have found yet another way to get everyone to listen once again, even when nobody is speaking.

COVID-19 forced us all to reimagine 2020, and for many youth activists around the U.S., the solution to the loss of this space was to create a new one. This has been characterized by the ongoing effort of youth activists to make world issues also campus issues, decentralizing the conversation around Black lives and police brutality to more deeply understand the experience of students of color on campus.

The emergence of the Instagram handle, @Blackat (insert an institution) has emerged at a time when our lives are virtual.

Now, as students can rarely host in-person protests or town halls, they have created anonymous and safe outlets to raise their voices. In the wake of the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, students of color are forcing universities, policymakers and white students to think of the system as the bullet (the thing doing the harm), and the students as the target practice (person being harmed)—this is to say that these oppressive systems are producing the same toxic cycles of trauma that result from police brutality against Black people. The difference is these oppressive systems are lined within foundational structures of academia.

If we understand the system of higher education to be a structural environment that is meant to produce whole-minded, intellectual and moralistic individuals, then we cannot neglect to also see the parallel of racism in the U.S. and the inherently racist system in which higher education was built.

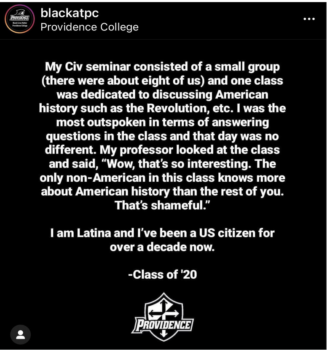

Examples of @Blackat__ from Providence College

Many higher education institutions emerged at a time when the U.S. education system lawfully excluded students of color—gave them a separate and an inherently unequal system, and forced them to believe the myth of their inferiority. This system has never been rewritten. It has simply been adjusted, amended and abbreviated. The social media handle @Blackat__ calls for the system of higher education to reimagine justice … to not simply add another bandage to the gaping wound of racism in the U.S., but rather, to reimagine a campus that is inherently inclusive regardless of race.

At the core of the @Blackat__ messages, students are simply sharing the stories that higher education has traditionally kept out of the narrative.

Have you ever asked a student of color how they felt about their predominantly white institution?

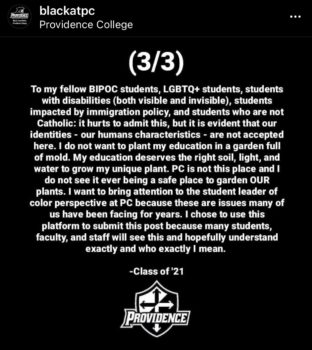

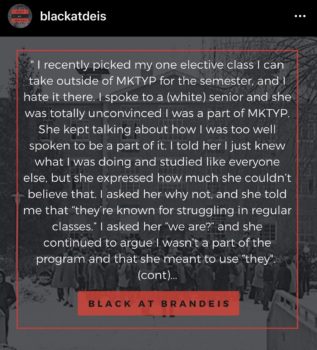

Example of @Blackat__ a PWI (Predominantly White Institution)

I would argue that their answer would hardly ever reflect the enthusiastic and heartful cheerleader role that white students often get to play, but rather, convey a conflicted statement of indifference. When I was in college, there was a time when we marked the days passing based on the last protest or sit-in. There were days when focusing on academics and standing up for ourselves were in direct conflict. So when many of us reached the end of those four years, we did not look back as fond alumni, but rather, as cynical and skeptical participants within higher education.

Too many students of color are still healing from the trauma that happened to them at PWIs. Many institutions now believe that the call for “establishing antiracist campuses” means that the stories of Black and other marginalized students are no longer the reality of students on campus. This is a mistake.

Example of @Blackat__ from Brandeis University

Instead of trying to negotiate the credibility of “antiracist initiative” by finding performative ways to show antiracism, these institutions should simply listen and learn and find ways to take definitive steps toward progress, not defensive steps away from it.

As Ibram Kendi writes, “There is no destination, it’s a journey of really consistently ensuring that we’re supporting antiracist policies and policymakers and that we’re articulating antiracist ideas, and we’re constantly unlearning this conditioning.” It’s time for higher education, for the academy—to finally act on these words.

Sara Jean-Francois is assistant director of NEBHE’s Regional Student Program, Tuition Break. She recently earned her master’s degree in public policy from Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management, where she conducted significant research on race-conscious campuses and issues of equity and inclusion in higher education.

Related Posts:

Attacks on Critical Race Theory Blemish Era of Race Consciousness

Will PWIs Embrace Change in a Nation at Unrest?

Higher Education Must Do Its Part to Bend the Arc

A New Plan for Faculty Diversity … and Other Winter Wonders from the NEJHE Beat

[ssba]