A Demographer Looks at New England’s Population and the Future of Education

A Demographer Looks at New England’s Population and the Future of Education

A great many New England institutions of higher education are about to find out if demography will determine their fate because unprecedented and substantial population change is sweeping across the region.

New England is demographically unique in a number of ways. With fewer than 15 million year-round residents, it is the nation’s smallest and one of the slowest-growing of the nine census divisions. In the past three years, this region’s population has edged up just 1.1%, which is less than half the rest of the nation’s growth rate.

This region is also demographically the oldest and most rapidly aging of the nine divisions. Its median age, which is now over 40, has risen by seven years since 1990. This region has six of the 12 states with the most rapidly rising median ages. Maine, Vermont and New Hampshire have the nation’s highest median ages (43.9, 42.4 and 42.3) and also rank first, second and third among the most rapidly aging since 1990.

Such high and rising median ages mean that two-thirds of adult women in this region are no longer in the child-bearing age range. The visible consequence of this rapid aging is a steady decline in the number of births and subsequent drop in the number of children in the region.

Between the 2000 and 2010 census, the number of children under age 18 in New England declined 197,000 or 6%. From the 2010 census until mid-2013 this region dropped another 102,000 children, and that rate of decline is projected to continue.

Each year since the last census, the Census Bureau has estimated the population of each state by tabulating the number of births and deaths and estimating the number of people that move in or out of each state. From 2010 to 2013, every New England state had more people move out than move in. In total, the region lost a net of almost 100,000 people through out-migration in just those three years.

Much of that out-migration comprises young adults who leave the region for what they perceive are better jobs and more affordable housing elsewhere. We can’t blame out-migration on bad winters. The simple fact is that most towns in the region have actively discouraged affordable housing on the belief that it will increase the school-age population and raise their property taxes.

Over the past two decades many towns in the region have encouraged, and in some cases mandated, homebuilders to construct age-restricted housing for residents aged 55 or older rather than affordable housing open to all ages. It turns out that excluding children is the only exception to longstanding federal regulations that prohibit age discrimination in housing.

Whatever the reasons, the most rapidly growing ages in New England are, by far, people aged 65 or older. That combined with the decline in numbers of children portend a very difficult decade for the region’s colleges and universities.

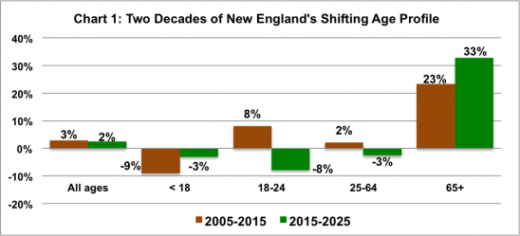

Each New England state has published a set of population projections which, when taken together show how the age profile of the region is likely to shift over the next decade. The chart below shows the estimated change in four major age categories over the past decade compared to the six states’ projections for the next decade.

Chart 1 paints a picture of continuing decline among children, but also forecasts a shift in the 18-to-24 age group and the 25-to-64 age groups from growth in the past to decline in the future. However, the past double-digit growth among residents age 65 or older is projected to continued at an even faster pace over the next 10 years.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau 2005 population estimates, New England states projections and author’s calculations

Cultural background

Behind this rather gloomy picture of a very slow-growing and rapidly aging New England population is the impact of its town-centered culture and the law of unintended consequences.

One of the unique characteristics of this region is it has very large number of (well over a thousand) small town governments, and the vast majority of them provide a full range of municipal services such as police, fire, road repair and public schools. By far, the most expensive of these public services is pre-K-12 education.

The result of having so many small local governmental entities is very high property taxes compared to other parts of the nation, where nearly all of the above public services are provided by larger counties. By contrast, the 67 New England counties provide almost no public services. Whenever efforts have been made to regionalize town services, such as school districts, to reduce property taxes the resistance has been very strong due to a widespread desire to maintain “local control.”

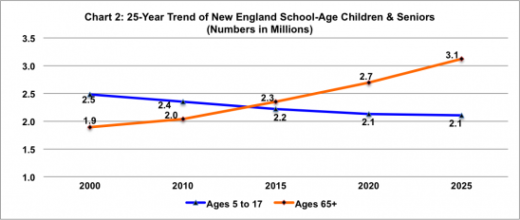

The unintended consequence of having so many very costly small school districts has been to create the perception among homeowners that children are an expensive burden to the local taxpayers rather than a long-term benefit to the community. Chart 2 shows the consequence of the belief that any housing where children live will raise your property taxes, but that housing restricted to age 55+ will not.

The New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority has commissioned several research projects that have proven conclusively that housing developments where children might reside do not in fact increase property taxes at all. But the belief that it does so persists to such an extent that it has become part of the region’s culture.

Source: Historical data is from the Census Bureau, population projections are by each New England state

Chart 2 also shows that the region is now at a tipping point where the number of elderly will increasingly outnumber school-age children. There is not much doubt that this trend will mean continuing erosion of financial support for local public education. It may also mean a gradual erosion in the quality of the region’s secondary schools and the consequent impact on those in higher education who depend on having a reliable source of college-ready high school graduates.

The fraction of households with any children under age 18 has reached an all-time low of about one in four here in New England. Passing a school budget or a bond issue for a new school becomes increasingly difficult when three in four households have no direct connection to the school system. Anyone attending a school budget meeting will almost certainly hear this refrain from an elderly homeowner: “I live on a fixed income and I can’t afford to pay any more taxes.”

This desire not to pay more taxes is part of the declining state support for higher education and has been documented by Tom Mortenson in the February issue of his newsletter Postsecondary Education Opportunity. In that issue, he describes the long-term decline of state fiscal support and suggests that one of the reasons is that “Higher education funding has been a lower priority than healthcare costs.”

This is clearly the case here in New England as the constituency for increased spending on healthcare is rising rapidly while those who might benefit from higher spending on state colleges are becoming a smaller share of the electorate. The Mortenson newsletter notes that New Hampshire spends the least of any state on its state colleges—only 30% of the U.S. average. But all six states in the region spend at below-average rates. Mortenson also extrapolates the decline for each state to the year when their support will go to zero—for most New England states, about 30 years.

The central question

Are the demographic trends described above going to define the destiny of New England colleges and universities, or not?

It depends on how these institutions act individually and collectively to craft development strategies to counteract what for some of them will soon enough become existential threats. A key point here is that demographic trends are well known and happen slowly enough and that there is time to understand why they are happening and what can be done to change their predicted outcome.

Here are three suggestions for consideration. First, each institution must document the sources of their incoming students and determine what is happening to the quality and quantity of those students. The demographic trends described above vary enough within the region that an institution that serves one state or a part of one will need to determine how the secondary schools in their service area are faring and how it might be possible to increase the number of students from those schools.

Second, New England colleges and universities collectively may need to ramp up a research project to find out the specific impediments that prevent young adults from attending a two- or four-year institution and getting a degree. The high and rising costs of going to college seem to be well known. Not as well known, or well-enough publicized, is the huge lifetime cost of not finishing high school or not having any education beyond high school.

Third, the digital revolution has added a significant layer of confusion about the value of online education. It would probably help prospective students if there were some well-documented research as to whether or not online education is a viable alternative to traditional classroom instruction. And under what circumstances it might become a valuable accessory to in-person teaching.

Most of the discussion above has been on the changing supply of young adult high school graduates. But in fact, there are millions of people older than age 18 who may have a desire or a specific need to attend a college or just take some college-level courses. The size, characteristics and needs of this older population of prospective college students will need to be better documented if they are going to replace the shrinking pool of young adults.

Perspective

The focus of this report has been on the region’s demographic problems that threaten higher education, without paying enough attention to the region’s assets. Chief among its demographic assets are very high levels of educational attainment and high family income. These are not inconsequential.

Most older people who have benefitted financially from having a college or graduate degree recognize that fact and appreciate the opportunity they had to get the degree. In New England, they represent a huge pool of affluent supporters who may need to be organized to help the region’s colleges and universities in this stressful time.

Here are some details: All New England states except Maine are on the list of 10 states with the highest percent of adults age 25 or older with a graduate degree: Mass. 1st; Conn. 3rd; Vt. 6th; R.I., 9th; and N.H., 10th. The Census Bureau’s 2012 survey found that the regional percent of adults age 25 or older with a bachelor’s degree was 36.5% compared with 29.1% for the nation.

The same survey found the median family income of the nation to be $83,100, compared with New England’s median of $101,900 in 2012. The region is indeed fortunate to have so many residents with such high education and income assets.

The task is how to imaginatively deploy those assets and other resources to address the difficult times ahead to secure a better future for New England’s institutions of higher education. In any event, there is no doubt that the survival of some of this region’s colleges and universities will require some very imaginative thinking.

Peter Francese is director of demographic forecasts for the New England Economic Partnership and founder of the former American Demographics magazine. He can be reached at peter@francese.com.

[ssba]

Great thanks for sharing. Actually they represent a huge pool of affluent supporters who may need to be organized to help the region’s colleges and universities in this stressful time. The task is how to imaginatively deploy those assets and other resources to address the difficult times ahead to secure a better future for New England’s institutions of higher education, whose survival will require some very imaginative thinking.