Whether and how campuses will reopen in fall 2020 has emerged as the key story in higher education. On Wednesday, Trump administration officials spoke via teleconference with higher education leaders on how to get students back to campus this fall.

Whether and how campuses will reopen in fall 2020 has emerged as the key story in higher education. On Wednesday, Trump administration officials spoke via teleconference with higher education leaders on how to get students back to campus this fall.

During a pandemic, we need to recognize that the risk assessment and risk tolerance among individuals and organizations varies dramatically. Those differences are not ones as to which we should be judgmental; we arrive at these assessments and tolerance levels based on data available and other objective information as well our own internal evaluations, many of which are informed by our experience, our culture and our previous exposure to trauma. In essence, risk assessment (more objective) and risk tolerance (subjective) lead to different outcomes when we face the same situations.

With the wide-ranging and varied reopenings that are now occurring across the country, we can now add a third element to the equation, namely risk management. For colleges that have decided they are reopening in fall 2020 with in-person classes and residential life, risk management is a task that moves front and center.

To reopen, these educational institutions have already made their risk assessment and determined their risk tolerance; the outcomes of that analysis have been the determiners of why they have decided to reopen. They surely recognized that the risks of reopening are not zero and to be fair, nothing in college life is risk-free. In the risk calculus of the reopening colleges (termed the “Reopeners” here), these institutions determined that benefits outweigh the risks. The question now becomes how to manage the risk.

This essay is an effort to reflect on how Reopeners can and should conduct risk management, which individuals need to be involved in the decision-making and what personnel within the institution will oversees compliance on a go-forward basis. Since there is time between now and September or October 2020 when the Reopeners doors will literally reopen, there is time to plan and reflect on how to manage their institutions safely, thoughtfully and in the most informed manner humanly possible.

Two caveats

First, there is something highly unusual about the risk calculi we are using to make decisions on reopening. The risks, which are something we can normally name and foresee with reasonable certainty based on past experience, is anything but certain. The risks of COVID-19 are new and changing as we come to understand more and more about the virus and its spread. We are only now seeing patterns in the individuals most at risk. We are only now getting a sense of whether cures and vaccines will be available and when. If one needs an example: consider the recognition that children are now being seen with a “novel” and serious illness that resembles Kawaski disease and toxic shock and seems to be connected with coronavirus. New information arriving daily makes decision-making on risk difficult, if not impossible. So, whatever risk calculi the Reopeners used, it is far from clear whether that’s the evaluation they need to make three months from now.

Second, I hope that Reopeners have the capacity within their institutions to change course and not reopen if and when the world changes enough to alter the risk they are willing to undertake. Indeed, one can have a hope and expectation about reopening and one can prepare for reopening. But I hope the Reopeners also have a Plan B and a Plan C for what happens if they cannot reopen and how they will handle all aspects of reopening. And if they reopen and the risk calculi change during the fall 2020 semester, I hope they have Plans D and E to address what they come to learn.

Managing risks by reopeners

There are a number of ways to manage risks and considerable literature on and risk management frameworks, none of which were created for a pandemic and reopening institutions of higher education. Adapting some of the existing approaches to risk management to Reopeners, what follows here are systematic ways in which to plan for the future of residential colleges. Note that some of this is applicable to non-residential colleges, although that is not the focus of this particular article.

In breaking this into steps, here are the key aspects of a reopening risk management architecture. But first, this is best explained visually. Imagine a pie on one side of the page. That, when divided into pieces, represents the myriad of constituencies that need to be consulted and then apprised of the results of any risk management plan. And, the number of slices is not small. Then, next to the pie is a basketball. The ball is tightly inflated and the inside of the ball, under pressure, is the educational Reopener institution. And the outside of the ball—the space it occupies and the counter-pressure it provides—is the community and larger world in which educational institutions sit.

Any quality risk management plan for reopeners must deal with the pie and the basketball with all the accompanying complexities, including pressure, balance, tension and intersecting and conflicting interests.

And to complete the visual representation, the basketball gets tossed, aiming for a net, which is the symbol of quality risk management steps. And the pie, it is just sitting there, waiting until it is eaten or tossed. Not a pretty picture.

Eight steps

Here are steps for reopeners to consider:

1. Identify and prioritize risks. On a campus, there are a number of risks that move across and within an institution. Risks related to the academic side of the house include: classroom set up and size of enrollment; engagement between faculty and students including office hours; types of group projects and internship opportunities. Risks related to the physical side of the house include: housing (need for single rooms); bathroom sharing; common entrances; shared congregating space; dining hall seating and service; student center space and its utilization; computer center space and its utilization; administrative access and meeting space. Risks related to the athletic side of the house include: practices; personal contact; games with or without fans; participation with and travel to other locations. Risks related to library: access to books; access to computers; use of space; presence of food and beverages. Risks related to parking: who gets to park and where; access for handicapped students/faculty/staff. Risks related to personal health both physical and mental: use of masks and by whom; determination of physical illness; determination of psychological struggles; presence of healthcare professionals in exam rooms and therapy rooms with sufficient distancing; waiting room protocols.

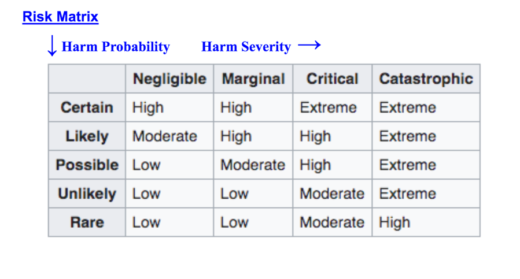

2. Strategies for ameliorating risks. In this context, investigation needs to examine how each identified risk can be ameliorated whether that is through, for examples, behavior, new equipment, new space redesign and cleaning procedures. Then, there need to be teams of personnel allocated to each group of issues with a point person. Vetting the approaches for every risk identified needs to be conducted, including with individuals not within that area of college life. For example, academic risks can also be evaluated by physical plant personnel. Student life issues can be evaluated by physical and mental health personnel. Once the amelioration has been proffered, then other parties need to engage in discussions and evaluations of the suggested approaches. This would be an iterative process. Each step needs to be charted next to the risk and then there needs to be a red, yellow or green designation: high risk, medium risk and low risk. Then the ameliorating actions need to be identified and measured: high, moderate or low effectiveness.

3. Responsibilities for initial design and ongoing oversight. There need to be clear delineations regarding who is doing what initially and then, on an ongoing basis, when reopening occurs. Once the ameliorating strategies are decided upon, that is the beginning and not the end of the process. There needs to be critical evaluation of compliance on a go-forward basis and some mechanisms for encouraging compliance and dealing with those who fail to comply, whether willfully or not. While tickets for absence of social distancing make no sense in an academic setting, there needs to be enough cultural change and peer pressure to ensure compliance and approaches to dealing with those who choose to put others (and themselves) at risk.

4. Identification of possible new hurdles and prospective risks. This phase is perhaps the hardest of those identified thus far. Reopeners need to predict what could go wrong with the identified risks above and then hypothesize as to new risks that could come into being and how those should be handled. For example, there needs to be a plan in the event of a virus outbreak during the semester that puts students, faculty, staff and administrations at risk of developing illnesses. Once flu season approaches, there need to be quality ways to assess the differences between the flu and COVID. And there need to be runways to collect new information that could affect campus life. For example, if there is a vaccine, how does one get it to all students, faculty and staff? If there is a quality antibody test, how does that get applied and to whom?

5. Communications plan. The need for a communications plan is critical, and key audiences may require different types of communication and different types of information. In addition, there may be needs for ongoing open communication channels so that as issues and questions arise, a mechanism is in place to handle them. One key feature here is to know the audiences with whom the Reopeners are communicating. In addition to communications with students, student families, faculty (full- and part-time), staff across the institution including contract vendors for services like alumni, the local community (perhaps in different groupings), religious leaders, the media (local and national). Social media outlets need to be monitored.

6. Reporting requirement considerations. There are many possible reporting requirements. First there are reports due to accreditors, which may shift in this economic environment in terms of the impact of a college’s finances on its continued accreditation. Second, there are local and state health reporting requirements, including cases of COVID. Third, there are likely going to be test-reporting obligations, including the results of tests for COVID and antibodies—one has to wonder how personal privacy will be preserved. In addition to these outside requirements, institutions may create their own reporting requirements: Does anyone on campus have a fever? How many students seek mental health or physical health counseling? How is student attendance across the institution, brick and mortar classes and online classes? How are retention rates?

7. Cost considerations. Surely the economic benefits for the Reopeners have already been assessed. Otherwise, why reopen if the costs exceed the benefits? Yet, there are considerable costs to Items 1–6 above and they must be calculated to evaluate both their efficacy and efficiency. Surely, now is not the time for Reopeners to shortchange the allocation of resources to the risk management initiatives. Indeed, the strategies are what enables opening. And they are not cost-free. These are not one-time costs either; continued monitoring, adequate health measures and offerings and monitoring compliance (and addressing non-compliance) are not cost-free. And in the event there are some changed circumstances, there are added critical costs to mitigate the situation. Communication too is costly and not a one-off. Ongoing communication is critical and affects prospective admissions as well.

8. Written diagram or chart of the above identified steps. What has been described thus far needs to be memorialized but this is not the time for a tome that will sit on a shelf unread. The written version of the risk management strategy needs to be short and clear and ideally, represented in visual form. And it needs to be widely distributed and available on the web. Whatever is published needs to state explicitly that the plan can be adapted when circumstances require. The latter point is an overt recognition that circumstances and assessment calculi can and may well change.

For an example of the type of diagram that could be used, see below:

Reopening by the Reopeners is not going to be easy and it is not risk-free. Surely it requires planning and flexibility and engagement of a myriad of constituencies in both formulating the plan but also in implementing it. My worry: The desire to reopen (one shared across our country) is fraught with risks. The Reopeners have a challenge to be sure, having made the decision that students, faculty and staff are welcomed back to campus. The overwhelming risk, in addition to students not enrolling and faculty and staff not appearing due to concerns of risk, is death. Who wants to be the Reopener in which there is an on-campus death? That is not a risk I would take were I a president. But this I know. If the risk is undertaken, risk management must be implemented in full force. Of that, I can be sure. Not much else is clear.

Karen Gross is former president of Southern Vermont College and senior policy advisor to the U.S. Department of Education. She specializes in student success and trauma across the educational landscape. Her new book, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door: Solutions and Strategies for Educators, PreK-College, will be released in June 2020 by Columbia Teachers College Press.

[ssba]