The earnings advantages to adults with more schooling are well-documented. High school graduates typically have higher earnings than high school dropouts, and those with a bachelor’s degree have higher earnings than both groups. Furthermore, as the job content of the nation’s economy has shifted in a way that generally favors those with more schooling, these earnings gaps between those with more schooling and those with less have widened.

The earnings advantages to adults with more schooling are well-documented. High school graduates typically have higher earnings than high school dropouts, and those with a bachelor’s degree have higher earnings than both groups. Furthermore, as the job content of the nation’s economy has shifted in a way that generally favors those with more schooling, these earnings gaps between those with more schooling and those with less have widened.

The policy response to these trends has been simple and straightforward—encourage more schooling—that is, an increased emphasis on high school dropout prevention, college enrollment for all high school graduates, and, more recently, an emphasis on college completion of degree and certificate programs. Measures of enrollment, retention and completion have become the North Star for judging the performance of the nation’s secondary and postsecondary education systems.

In recent years, the emphasis on these measures has resulted in improvements in on-time high school completion rates (8.5 percentage points increase from 2005-6 to 2012-13), a narrowing of race-ethnicity gaps in postsecondary enrollment (White/Black/Hispanic rate gap declined by 8 percentage points from 2005 to 2013), and rising college completion rates (four-year completion of entering freshman cohort rose 3.5 percentage points from 2005 to 2011), according to federal data.

However, the growth in diploma, certificate and degree attainment has not been accompanied by commensurate improvements in the most fundamental skills: literacy and numeracy.

At the secondary level, as we see high school retention and on-time completion rates rise, the share of students who are considered to be academically prepared for college coursework has declined. The share of 12th grade students who scored proficient or better on the NAEP math and science measures ranged between just 20% and 30%. An international comparison of math skills found U.S. millennials (aged 16 to 34) ranked last among 22 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries on the recent Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) survey of adult skills. The literacy score of U.S. millennials ranked them at No. 16 among their counterparts from 22 developed nations.

So what does this mean about the labor market rewards to earning a high school diploma or a college degree? Do the large earnings advantages mean that we should place a laser-like focus on retention and completion?

New evidence from the PIAAC survey of adult skills in the U.S. indicates that most studies overestimate the returns to schooling. This overstatement occurs because most national surveys that are used to produce these earnings returns to educational attainment do not have separate measures of literacy and numeracy proficiencies—foundational skills that are highly valued in the labor market. (Literacy and numeracy are also closely and positively connected to measures of health status, civic engagement and other social outcomes that are not measured by earnings.)

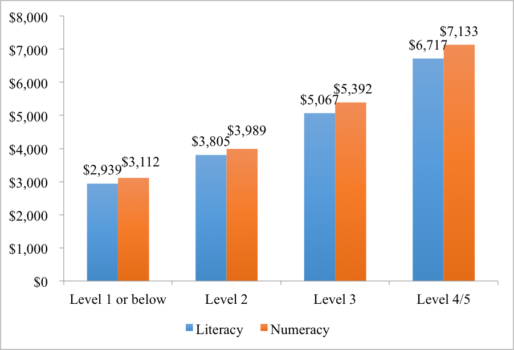

Using PIAAC data files, we analyzed the earnings of full-time and prime age (25-54) workers that comprise the “core” of the American labor market in a recently released report by the Educational Testing Service (ETS), Skills and Earnings in the Full-time Labor Market. We found that, like educational attainment, higher levels of literacy and numeracy skills are closely associated with higher earnings—a finding also reflected in the ETS’s 2015 report America’s Skill Challenge: Millennials and the Future.

But skills have a strong influence on earnings that is independent of the level of attainment.

The average monthly earnings of workers with the highest literacy scores (levels 4/5) were 77% higher than the mean earnings of workers with level 2 literacy scores. Workers with numeracy scores at level 4/5 had mean monthly earnings that were 79% greater than that of their level 2 counterparts. Level 4/5 literacy requires the ability to integrate information across multiple dense texts and make complex inferences. In contrast, level 2 literacy requires individuals to make low-level inferences, from non-dense texts and navigate and locate information in a document.

Figure 1: Mean Monthly Earnings of Full-Time, Prime-Age Workers in the U.S., by the Level of Literacy and Numeracy Skills

Although educational attainment and literacy and numeracy skills are positively correlated, they are far from perfectly correlated. Figure 2 provides a distribution of full-time prime-age workers within each educational group by the level of their literacy and numeracy proficiencies. As one would expect, the share of workers with strong literacy and numeracy proficiencies (level 4/5) rises with the level of educational attainment. This result is not surprising since advancement within the education system is associated with higher foundational skills.

However, what might be surprising is the substantial share of full-time working adults who failed to achieve level 3 literacy and numeracy scores—considered a minimum standard for literacy and numeracy proficiencies that is associated with positive economic social and educational outcomes. PIAAC data reveal that two-thirds of adult full-time employed high school graduates had below level 3 literacy scores and 77% had failed to achieve a level 3 numeracy score. Perhaps of even greater concern is the large shares of these full-time employed high school graduates with very low literacy and numeracy scores; more than one in five had literacy scores at or below level 1; and worse still, more than one-third had numeracy scores at or below level 1.

Figure 2: Distribution of Full-Time, Prime-Age Workers by Educational Attainment and the Level of Literacy and Numeracy Skills

| Literacy | Numeracy | |||||

| Level 2 or Below | Level 3 | Level 4/5 | Level 2 or Below | Level 3 | Level

4/5 |

|

| No HS Diploma | 92% | 8% | 8% | 94% | 5% | 1% |

| HS Diploma Only | 67% | 29% | 5% | 77% | 21% | 3% |

| Some College, without a degree or certificate | 41% | 45% | 13% | 57% | 36% | 8% |

| Postsecondary Certificate | 47% | 44% | 9% | 61% | 30% | 9% |

| Associate | 36% | 48% | 16% | 49% | 41% | 10% |

| Bachelor’s | 18% | 52% | 30% | 29% | 47% | 24% |

| Master’s or higher | 13% | 45% | 41% | 21% | 45% | 34% |

Even among those who had earned a college degree, a substantial numbers of college graduate workers had literacy and numeracy scores below levels that most colleges would expect their graduates to possess. More than one in three full-time, prime-age workers with an associate degree had literacy skill scores below level 3 and about half had numeracy scores below the minimum standard (level 3). Among those with a bachelor’s degree, 18% had literacy scores below the minimum standard and 29% had numeracy scores below this standard (level 3). Advanced degree holders (with a master’s, doctorate, or professional degree) also had substantial skill deficiencies. One in eight advanced degree holders had below level 3 literacy skills, and one in five scored below this minimum standard on the numeracy test.

Our analysis of PIAAC data reveals that workers with low skill levels have substantially lower earnings than their higher skill counterparts even with the same level of educational attainment. Our statistical analysis reveals substantial earnings gains to literacy and numeracy skills even after holding constant the effects of educational attainment, years of work experience, and other key worker traits and job traits. The result should not be surprising, as employers are interested in diplomas and degrees insofar as they signal the productive capabilities of job applicants. In this information age, literacy and numeracy skills are the sine qua non for labor market success.

This does not mean that educational attainment is unimportant. Completing high school and college has sizeable positive influences on employment and earnings, as well as a host of personal, familial and civic life outcomes. But degree and diploma attainment with attenuated skill achievement diminishes the fundamental promise of education. “Access to literacy” lawsuits are now proceeding in several states on the premise that state and local educational authorities have failed to deliver on the promise of foundational skills for many students.

The education reform effort at the elementary and secondary school level that began in the early 1980s, and was first introduced in New England in 1993 with the reform legislation in Massachusetts, was driven by the objective of bolstering the literacy and numeracy proficiencies of students. In recent years, dropout prevention and college-for-all programs have taken center stage in the education policy arena. But the labor market will reward the additional diplomas and degrees created by such policies only if they are backed by strong foundational (literacy and numeracy) skills that are valued in the job market.

The complete report “Skills and Earnings in the Full-time Labor Market” is available at https://www.ets.org/s/research/pdf/skills-and-earnings-in-the-full-time-labor-market.pdf

Neeta Fogg is research professor at the Center for Labor Markets and Policy at Drexel University. Paul Harrington is director of the center. Ishwar Khatiwada is an economist there.

For a sampling of previous NEJHE articles by Fogg and Harrington, click here.

[ssba]