The relationship between employer and employee has changed significantly over the past 40 years. One of the greatest changes in this relationship is in the nature of employee retirement.

The relationship between employer and employee has changed significantly over the past 40 years. One of the greatest changes in this relationship is in the nature of employee retirement.

While pension reform at public and private colleges has helped ensure institutional financial viability, retirement security for employees has declined. With the redirection of retirement plans from defined benefit programs toward defined contribution plans for employees, the onus is on higher ed employers to be sure that employees are well-prepared for life after college.

Using Rhode Island as a case study, we explore several “early interventions” that employers can make to help employees financially prepare for retirement and thereby improve retirement readiness.

Risk and retirement

Defined benefit plans—while traditionally the most secure pension option for employees—are quickly fading from the American economy in favor of defined contribution plans, which typically involve less liability for employers and place more personal responsibility on the employee.

Defined benefit plans generally pay lifetime annuities for retired employees, and sometimes their surviving spouses, based on wages and overall time spent at a particular organization. In this structure, employees have the benefit of predictable incomes, whereas employers face considerably more liability because of the risks involved in budgeting for their employees’ unknown lifespans.

Prior to the Great Recession, most public-sector employers used defined benefit plans, and these obligations have resulted in huge unfunded pension liabilities, the extent of which was largely unknown until after the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) started requiring the public sector to include these numbers on their balance sheets in 2012. The Pew Charitable Trusts reports that in 2014, the gap for states between their accrued assets set aside and their benefit obligations was $934 billion. Another study by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College looked at a sample of 173 major U.S. cities and found that in 2012 unfunded pension liabilities amounted to $177 billion.

States and institutions have tried to limit the scope of this problem by moving away from defined benefit plans. An often-cited statistic has it that in 1983, more than 60% of American workers had some kind of defined benefit plan; in 2012, it was less than 20%. Instead, employers are opting for defined contribution plans that allow employees to save in retirement accounts like 401(k)s or 403(b)s. Under this model, employers have a much clearer understanding of their financial obligations. In most cases, they commit to matching a certain amount or percentage of employee salary every pay period. Importantly, there are no future obligations, and the employer may even get some of the matching contributions back if the employee does not remain with the organization through a vesting period.

For employees as well, defined contribution plans have certain advantages. Because these plans exist separate from the employing organizations, they are far more flexible than defined benefit plans. Employees who transition in and out of the public sector, or in between states, are able to retain control over their retirement savings. The desire for flexibility makes sense given the realities of the labor market. New figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that in January 2016, median employee tenure with their current employer was only 4.2 years.

And yet, along with flexibility comes risk. In defined contribution plans, the risk of investment performance is entirely the responsibility of the employee. Not surprisingly, as traditional pension plans have been largely phased out, retirement readiness has declined. A recent survey estimates that one in three Americans has saved $0 for their retirement, and 75% of Americans over age 40 are not on-track with their retirement savings. Even those who are on-track face the risk that their future returns will be less than they planned for. Immediately following the 2008 stock market crash, for instance, retirement accounts lost $2.7 trillion collectively, nearly a third of their value. While retirement accounts have seen substantial gains since the Great Recession, recent projections indicate that returns for the next 10 years may be lower than expected, potentially creating shortfalls for employees.

This offloading of risk represents a fundamental shift in the social compact between employer and employee. Defined benefit plans were long-term commitments often used as incentives both to recruit employees and to keep them. Employees’ commitments to support the company/institution during their working years were matched by employer commitments to support employees after their working years as long as they lived and even, in some cases, as long as their surviving spouse lived. Defined contribution plans, however, seem much more transactional and finite. Employers may make contributions toward retirement accounts each paycheck, but the employees must make the tough calculations about how long they might live and how much money to sock away now to sustain themselves and their families.

Even as employees shoulder more of the risk in preparing for retirement, employers still have a moral obligation to steward the success of their employees. In other words, we must be sure that the defined contribution approach produces a benefit that can sustain our employees through retirement. Many colleges already help faculty and staff in their careers by providing incentives for publishing, receipt of research grants, or active involvement in academic organizations. These incentives have shown to increase faculty research and professional development. College leaders, however, have tended to intervene less in preparing employees for life after college.

Recent court decisions make this more than a philosophical position. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Tibble v. Edison International (2015) that retirement plan sponsors had a continuing duty to monitor their pension programs and investments and remove imprudent options. MIT, NYU and Yale are facing litigation based upon the claim that they allowed employees to be charged excessive fees on their retirement savings, and a second round of lawsuits includes even more institutions.

What is more, helping employees become more financially secure may boost an organization’s productivity and retention. According to the 2015/16 Global Benefits Attitudes Survey, 46% of workers over age 50 believe that they will have to work past age 70 in order to save enough for retirement, and 40% of employees feel stuck in their current jobs. Those who delay retirement are more likely to be disengaged and in poor health, making them less productive, whereas employees tend to be more engaged and less stressed when their employers actively work to provide post-work financial security.

One state’s approach

Strategies for reconfiguring state pension plans vary greatly. Rhode Island has had some success in restructuring its plan to balance risk for the employer and employee. The “Rhode to Retirement” hybrid pension plan was a product of the Rhode Island Retirement Security Act (RIRSA), passed in 2011. This plan replaced the state’s defined benefit pension plan with a new system based on the combination of a new defined contribution plan and a smaller defined benefit percentage. Under this plan, the state puts 3.75% of the employee’s base salary into a defined benefit account, and in addition, depending on the employee’s years of service and assuming the employee is eligible for Social Security, contributes 1% to 1.5% of their salary to a defined contribution account, while the employee invests 5% to the same defined contribution account.

In addition to this new retirement savings system, changes were made to benefits received by newer workers, such as raising the retirement age from 62 to 67, reducing the defined benefit accrual rate, and mandating that all retirees be required to enroll in Medicare after age 65. In this hybrid pension plan, state employees are able to maintain some of the security they had under the previous pension plan, while having the ability to tailor their portfolio to their investment preferences and retirement expectations. The defined contribution account remains available to the employee if they change jobs, even if that job is outside the public sector.

Rhode Island’s postsecondary education system has a two-tiered retirement program. Classified employees who work 20 hours or more per week are enrolled in the state hybrid retirement plan, while non-classified employees, faculty and professional staff are eligible only for a defined contribution plan through their institution. Under this plan, employees must contribute 5% of their salary to a defined contribution account with one of three plan providers. The institution then contributes 9% of the employee’s salary to the account, and there is no vesting period. Employees also have the option to make additional contributions beyond the requisite 5%. Employer contribution percentages to this plan are twice as much as the 2013 national average of 4.5%.

Even with a generous employer contribution in place, some Rhode Island postsecondary employees still struggle to build a nest egg big enough to sustain them through retirement. Aggregated data from one provider shows that of the 5,679 total participants in Rhode Island’s higher education agreement with that provider, about 52% of the employees are considered “Non-Contributing Participants” (NCPs). This means that those 2,962 employees are no longer adding to their balance in the account. The remaining 48% (2,717 employees) are considered “Active Participants” (ACPs), meaning additional contributions from the employer, employee or both are being put into their accounts.

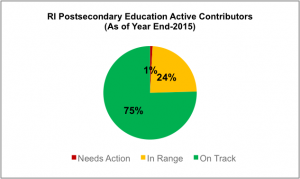

The provider analyzes these active participants’ balances, behaviors and investments relative to their individual actual or estimated salary (actual salary improves the accuracy of the projected retirement income) to determine what percentage of the pre-retirement income the employee is projected to replace in retirement. Employees are considered “on-track” to retire when they have a high probability of being financially prepared to live a relatively similar lifestyle after they stop working. An analysis of 2015 data shows that one-in-four are at risk of not being able to maintain a similar lifestyle in retirement.

Employees who are “on track” have a high probability of maintaining most of their pre-retirement income in retirement, and some may even be able to exceed their pre-retirement income levels. It is important for these employees to continue on their savings and investment path until retirement. The “in range” group of employees is less likely to maintain their lifestyle by staying on their current course, and those that “need action” have a high-probability of only being able to replace 60% or less of their pre-retirement income when they stop working. The fact that as many as 25% of employees remain underprepared, even with key system interventions in place, means more can be done, and this is doubly true for institutions that are less generous in their defined contribution plans.

Intrusive advising for employees

College leaders are familiar with the idea of intrusive or proactive advising for their students. Campus staff members optimize the success of students by stepping in at key transition points in their academic journey and in areas where there are indications that they need some support. This model has become common practice on campuses across the country, and has earned a reputation for its proven success. Each transition point carries a risk that students will get “off-track” and interventions are necessary to keep them “on-track” toward their goal of graduating with a degree. The first semester transition is known to be very important in the lives with college students. Institutions monitor student attendance and provide midterm grades to students in courses dominated by freshmen so they can identify who needs help and in what manner. Institutions concern themselves with students registering for the following fall and make sure they do return for the fall term. They also establish admission requirements for students entering particular academic programs that ensure their future success. Many programs also have the seminal courses that allow students to prepare portfolios and gain work experience to assist the transition from school to work. All of these activities are designed to prepare college students for their life after college.

But what is it that institutions do for their employees?

In every employee’s life there are also key transition points, like joining the institution, getting a promotion or moving to a new organization. As in the model of student advising, intervention at these key points can help keep employees on track toward their financial goals. Just as students need help developing habits of studying, employees need help developing habits of saving.

Perhaps the most important transition point is when a new employee first decides how much of their earnings to direct toward their defined contribution accounts. Many 401(k) defined contribution plans fall short because of inadequate or nonexistent contribution rates. Like college freshmen, new employees often find themselves faced with competing priorities and may not allocate enough resources toward their long-term goals. Myopic spending early in one’s working career, whether on college expenses or housing, creates a shorter expanse of time the worker has to invest. This myopia-induced delay makes it more difficult to achieve an adequate accumulation of savings later in the life cycle. In addition, many employees report that they don’t join the retirement plan because the enrollment process is just too hard to figure out. Sound familiar?

Actively planning for retirement and simplifying the enrollment process can help to mitigate these factors. Research on decision-making for retirement has found that heads of households who had not engaged in planning activities had built significantly less retirement capital than their counterparts who had done some planning. A savings intervention study by Oklahoma State University scholars found that goal-oriented, group-based retirement seminars had a significant impact on planning activities the year after the intervention. Providing adequate financial advising for new employees will help to ensure that they engage in planning and goal-setting as early as possible.

Moreover, new employees are often confronted with a significant number of investment options for their defined contribution plans, which ironically can be a detriment to investing. Behavioral economists have conducted studies on the effects of “choice overload” on retirement investing and found that for every 10 additional investment options, participation in any retirement plan dropped by about 2%. More concretely, when two plans were offered, 75% participated; when given 59 plan options were offered, the participation dropped to 60%. Choice overload is not just a matter of having too many options to choose from, but also not having enough information to choose among them. This body of research points to a number of adverse behaviors that result from an overabundance of choice. It can cause a decrease in the motivation to choose or commit to a specific plan, a decrease in preference strength and satisfaction, and an increase in disappointment and regret with their decision. Proper financial advising can help employees identify retirement options that suit their goals.

Even if individuals are contributing enough to their defined contribution plan, poor investment strategies can hold them back, and these effects are magnified over time through the power of compound interest. Just as predictive analytics have helped academic advisers identify which students are at risk of dropping out, financial modeling can help identify which employees are not on track to retire so that advisers can help them make proper adjustments.

One profile of “at-risk” investors includes those with risk-averse tendencies early in their careers. According to a 2014 Gallup survey, as many as 64% of investors prefer to steer clear of stock and bond options that are perceived as producing volatile returns in favor of options with a lower but secure rate of return. Yet, over the long term, higher risk options tend to give the greatest returns. In their attempts to avoid risky investments, defined contribution plan participants often over-invest in conservative options, such as fixed-income options—a trend which is especially true for low-income and minority employees. On the flip side, those nearing retirement can put themselves at risk with portfolios that have too much volatility. Rather than investing in stocks and bonds, they would be better served with fixed-income options that produce a steady rate of return and allow them to predict their retirement income more accurately. Another “at risk” profile includes investors with a lack of diversity in their portfolio, which leaves them exposed to even minor fluctuations in the market. A number of investors may attain the vast majority of their shares from local corporations, thereby relying too heavily on one or a few. Studies have shown that low-income workers with defined contribution plans are three to five times as likely as their higher-income colleagues to have more than 80% of their retirement savings in one stock.

Working closely with a financial adviser can help an at-risk employee redirect their investments toward those that suit their age, risk tolerance and engagement level. For instance, financial advising companies have tried to address these poor investment strategies by creating life-cycle funds. These mutual funds are designed to provide diverse investments that adjust over time. Early on, the funds tend to have a riskier portfolio of equities, and then shift to more conservative options over time as employees would near retirement. Financial advisers can also help investors make informed decisions about fees associated with certain investments. By virtue of the compounding effect of interest over time, even marginal increases in fees can have a dramatic impact on cumulative retirement savings. In a typical example, a one percentage point increase in fees over a 35-year career could leave a worker with 28% less revenue at retirement.

Finally, intervention is recommended for anyone who has gone three years since attending an advising session because people typically do not adjust their contribution amounts or investment strategies in response to various market phenomena or life stages.

Tools and education

College and university leaders must take the lead in providing employees with the tools and education to save and invest in appropriate retirement portfolios. With less than half of America’s workforce “ready” to retire, the time is optimal for creating change in the way employers provide retirement benefits to their employees.

It is possible for defined contribution plans, such as the plan that Rhode Island higher education institutions currently participate in, to produce better outcomes for employees than defined benefit plans historically have. In order to provide successful returns for the employee, intensive investment training and education is critical, and should be made at key points for all non-classified higher education employees. It is recommended by the Rhode Island Office of the Postsecondary Commissioner that colleges partner more closely with retirement agencies to provide intrusive financial advising to all employees, especially new employees and those deemed “at risk” in saving for retirement. In this way, college leaders will guide individuals to actively and successfully save, and no longer worry about their life after college.

James Purcell is Rhode Island commissioner of postsecondary education. Robin McGill is a specialist in public information and communications in the RI Office of the Postsecondary Commissioner. Philip Brodeur is a graduate student in higher education administration at Columbia University. Erin Hall is a research intern in the RI Office of the Postsecondary Commissioner.

[ssba]