As the lowest-priced higher education institutions serving the greatest share of students in New England, public institutions are a crucial access point for the region’s students who may not have other opportunities to enroll in college. Maintaining the cost of attending a public institution in New England is imperative for students, families, communities, states and the region. Yet, the price of public higher education rose dramatically since the beginning of the 2008 recession.

Meanwhile, five of six New England states face multimillion-dollar budget shortfalls this fiscal year. State policymakers who must simultaneously address current deficits and decide on upcoming budget plans have tough choices ahead. Funding for public higher education is one of many competing budget priorities. With few federal or state regulations on minimum funding levels, allocations to higher education are frequently cut to create a leaner budget.

As the region strives to grow beyond modest “recovery” from the Great Recession, however, a robust, high-quality system of public higher education is vital. The Georgetown Center on Education and Workforce predicts that 65% of jobs will require some education beyond high school by 2020. In the New England states, the projected number of jobs requiring some postsecondary education is equal to or higher than the national projection. A more educated labor force is needed if New England states are to continue to develop a competitive economy. A more educated labor force would also improve residents’ quality of life, and, not coincidentally, relieve pressures on state budgets in other areas such as corrections and healthcare. Getting there, however, will require accessible and affordable quality higher education options for students.

Public higher education plays a critical role.

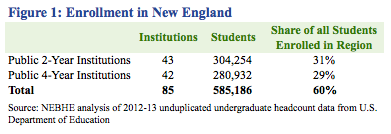

New England’s public institutions serve a majority of the region’s college students—60%, or nearly 600,000 undergraduates, in academic year 2012-13 (Figure 1).

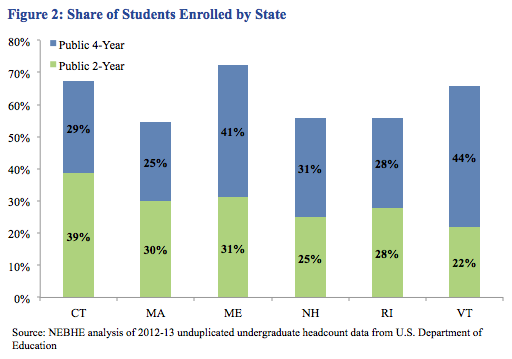

Across states, the breakdown of enrollments varies across sectors (Figure 2).

- The share of all students enrolled in public 2-year institutions ranged from a low of 22% in Vermont (though this excludes a predominantly 2-year institution that also awards 4-year degrees) to a high of 39% in Connecticut.

- The share of all students enrolled in public 4-year institutions ranged from a low of 25% in Massachusetts (a state with more than 80 private colleges and universities) to a high of 44% in Vermont.

- With 42% of all students enrolled in the public 2-year sector across the country and 33% of students enrolled in the public 4-year sector nationwide, the region enrolls a smaller share of students in public institutions than the nation overall.

Prices of public higher education rose dramatically since the beginning of recession.

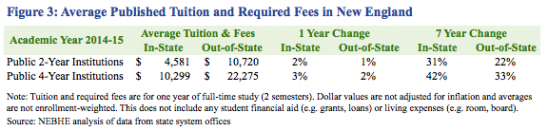

This academic year (2014-15), average published tuition and mandatory fees for a year of full-time study in New England is $4,581 at public 2-year institutions and $10,299 at public 4-year institutions (Figure 3).

Prices for both sectors are well above the U.S. averages of $3,508 for 2-year institutions and $8,471 for 4-year institutions. Yet tuition increases in New England’s 2-year sector have been slower over the past seven years than nationwide, showing promise for the region’s community colleges—a crucial access point for residents.

- After years of dramatic tuition hikes, many public institutions have frozen—and in some cases, reduced—tuition and fees. On average, tuition and fees at 2-year and 4-year institutions increased only modestly from academic year 2013-14 to academic year 2014-15 for both state residents and out-of-state students. For in-state students, this represents a $74 increase at 2-year institutions and a $265 increase at 4-year institutions.

- Tuition and fees are still dramatically higher than before the recession. Published tuition and required fees climbed 42% ($3,024) for the 4-year sector between academic year 2014-15 and academic year 2007-08 (a seven-year change). Prices rose nearly a third ($1,071) for the 2-year sector over this period.

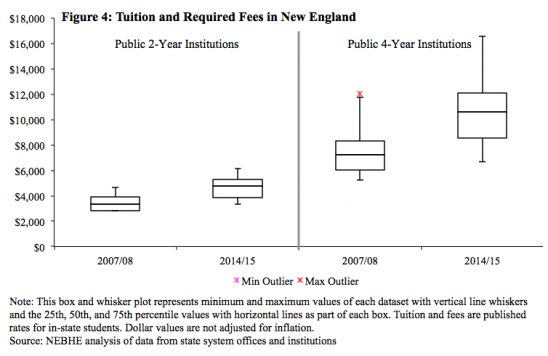

Price increases varied across public 2-year and 4-year sectors (Figure 4). With a greater diversity of institutions in the 4-year sector (online-only, bachelor’s-, master’s-, doctorate-granting), the range of lower- and higher-priced options is larger, and the change in median tuition and mandatory fees (the solid black line in the middle of each box in Figure 4) is more substantial.

These changes disproportionately impacted low-income families.

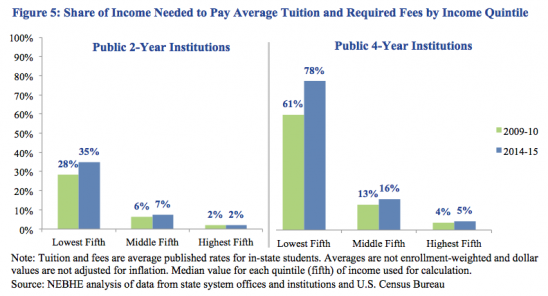

Over the past five years, published tuition prices have risen faster than household income, leaving most New England families to direct a larger share of their income to pay for college. (Figure 5)

- For families in the lowest income quintile in 2014-15, paying for a year of full-time study would require 35% of annual income at a public 2-year institution, or 78% at a public 4-year institution. These figures are dramatically higher than the shares of income required for the middle- or highest-income quintiles.

- Declining incomes for families in the lowest income quintile exacerbated the impact of rising tuition and fee rates in the region. While the middle and highest quintiles saw an increase of 1 to 3 percentage points, the lowest quintile experienced increases of 7 percentage points at 2-year institutions and 17 percentage points at 4-year institutions.

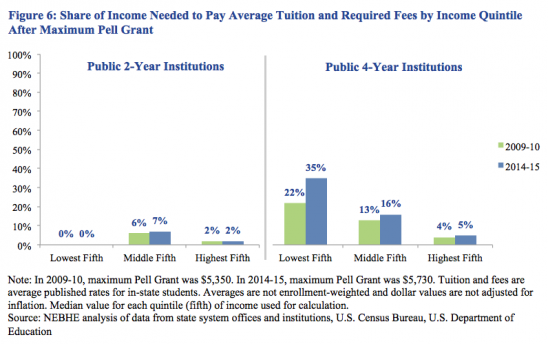

Of course, not all students rely on family income to pay for college. The majority of students seek some kind of financial aid—81% of students filed a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) in 2014, according to a recent Sallie Mae survey. Financial aid lowers the share of income needed to pay tuition, though this varies significantly between students and institutions. While individual student financial aid packages vary, at least one financial aid program is fairly easy to predict and summarize: the federal Pell Grant. Receiving the maximum Pell Grant award would lower the lowest quintile’s share of income needed to 0% at 2-year institutions and 35% at 4-year institutions (Figure 6).

The stark difference in cost burden on the lowest quintile of households after including the maximum Pell Grant speaks volumes to the power of financial aid. When funded and targeted effectively, grants and scholarships can level the playing field between high- and low-income students in terms of share of income needed to pay tuition and fees. In fact, many New England states are currently investigating how to maximize the effectiveness of their own financial aid programs through NEBHE’s Redesigning Student Aid in New England project, legislative study commissions and other efforts.

Financial aid alone, however, may be an unsustainable solution to addressing affordability concerns in the region. Transformative change in costs and prices passed on to students is needed if public institutions aim to continue as New England’s affordable, most accessible pathway to a postsecondary credential.

Recent attempts to revolutionize paying for college include America’s College Promise, President Obama’s recent proposal to make community or technical college “as free and universal as high school,” the Tennessee Promise scholarship, the City University of New York’s holistic ASAP program, and Pay It Forward proposals. NEBHE’s Higher Education Innovation Challenge goes directly after institutional cost issues. The country is on the precipice of bold, groundbreaking action; New England states have the chance to lead the way.

As a data-rich companion to On Affordability, please see the 2014-15 Public Tuition and Fees Data Supplement, which provides a portfolio of figures that track and examine tuition and fees for both the region overall and each New England state.

Gretchen Syverud is a policy research analyst at NEBHE.

[ssba]