Shifting demography, rising operating expenses, plummeting state and federal support, intensified competition, broken financial models … these are just a few of the complex challenges facing New England higher education institutions. Given these tensions, who would be surprised if college presidents in the region weren’t occasionally plagued by sleepless nights, hounded by anxious trustees, or passing a few furtive moments hiding beneath their desks?

Shifting demography, rising operating expenses, plummeting state and federal support, intensified competition, broken financial models … these are just a few of the complex challenges facing New England higher education institutions. Given these tensions, who would be surprised if college presidents in the region weren’t occasionally plagued by sleepless nights, hounded by anxious trustees, or passing a few furtive moments hiding beneath their desks?

The reality, though, seems to be moving in a different direction altogether—at least as reported by area presidents themselves. We recently conducted an admittedly non-scientific “pulse” survey1 of presidents at smaller institutions in the New England region. A high percentage of these presidents feel much more confident in the face of these challenges than some might reasonably expect.

Respondents to our survey appear to agree that new models are needed to ensure the sustainability of smaller New England colleges. But they also possess confidence in the capacity, agility, and talent of their people to successfully create new models, with few worries that the needed changes will put them at odds with their institutions’ missions or values. That’s the good news. Indeed, there seems to be widespread agreement on what to do to become more sustainable—change the financial model, lower discount rates, reach new audiences through online learning and strengthen the institution’s competitive differentiation.

The bad news is that while a universally applied strategy like this could perhaps work in an ever-growing market, in New England, the opposite is likely to be true. Our region will be characterized by intensified competition for a shrinking pool of prospective students. Even in the realm of online learning, growth rates are declining as competition heats up, with no infinite market to tap for new students. So while strategies such as these may work for some of our colleges, they cannot logically work for all at the same time, especially those smaller schools without resources to extend their reach.

Time will be a crucial factor in determining how these strategies play out for individual institutions. While presidents might feel bullish about the capability of their faculty and staff to innovate, some institutions will execute changes more quickly and effectively than others. For those that move more slowly, the result could look something like a game of musical chairs: When the music stops, a few may find that they are no longer in the game at all.

Taking the stress test

Our concise survey of presidents of smaller colleges throughout New England took the form of a 10-question “stress test” that gauged how apprehensive institutional leaders feel about the fate of their schools and New England’s overall academic hegemony.

We invited them to reflect on their pressures from trustees for a strategy for online education, whether they felt their faculty could demonstrate the flexibility and creativity for the institution to thrive in the future, whether ideas about alternative revenue streams might be at odds with their institution’s mission and values, and whether the small New England college was fundamentally at risk.

Two-thirds of the presidents surveyed said their trustees expected them “to rapidly develop a more advanced strategy for online education.” Trustees read newspapers and magazines, and see the barrage of articles forecasting the demise of higher learning as we know it.2 They read the simplistic and often alarmist op-ed pieces that conflate online learning and all the challenges colleges and universities face. They then take these concerns back to board meetings and conversations with their president, and ask what it is being done to steer their school on a path to survival.3

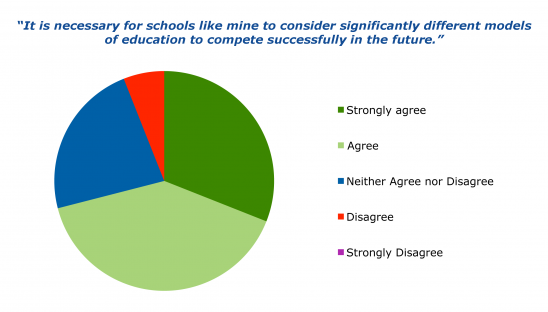

The presidents do not necessarily take exception to these concerns. Only 6% disagreed with the statement that “it is necessary for schools like mine to consider significantly different models of education in order to compete successfully in the future.” They are open to change and new modes of operating. “The world’s strongest colleges and universities are in New England,” wrote one president. “I expect that fact to remain salient for many years to come. Yes, we all must adapt as conditions around us change. A few institutions will not adjust and will close, but not many. Colleges have proven to have incredible staying power, backed by the emotional attachment of their many alumni and supporters.”

The presidents themselves often have a broad perspective of what academic tremors are occurring nationally across the array of America’s institutions. They know how precious and fragile the smaller college is They fear these small colleges might be endangered by forces beyond their control and by their vulnerability to academic behemoths.4 One president with extensive experience across different types of universities noted: “I am particularly concerned about the long-term viability of smaller, not-for-profit institutions. Many are without name recognition or endowment to allow them to weather the impending storm easily. Many are at risk because their financial model, organizational structure and physical plant requirements will make it difficult for them to easily change. More will need … to partner with other institutions so they don’t … provide all curriculum in-house. In addition, they will need to look at the tenure model versus long- or short-term faculty contracts.”

This adaptation may not be as rapid as trustees want, but New England presidents are hopeful for their own institutions. Two-thirds said it will take time to build a thoughtful strategy that incorporates educational technology. Only 40%, though, were critical of other schools for jumping recklessly into expensive educational technology. While presidents commonly turn to faculty-bashing when asked why colleges cannot be more dynamic, New England’s small college presidents praised their own faculty. Only 9% did not agree that their faculty demonstrated “the flexibility and creativity that will help us thrive in the future.” Rather than caricature their professors as resistant and self-serving, they view them as willing and able partners in the process of institutional evolution.

Finding the path to sustainability

The changes these institutions appear prepared to make will be significant. The very preservation of smaller schools is at stake. As one president wrote to us: “There are students who need the structure of a small college in order to discover their talents and strengths. As an industry, we need to be more aggressive at finding ways to tell the story of the value of a college education and the importance of education for the future of the American workforce.” The public needs to better appreciate that the small institutions are treasures worth preserving–that these schools offer unique benefits that would be lost if we dramatically consolidated our academic institutions.

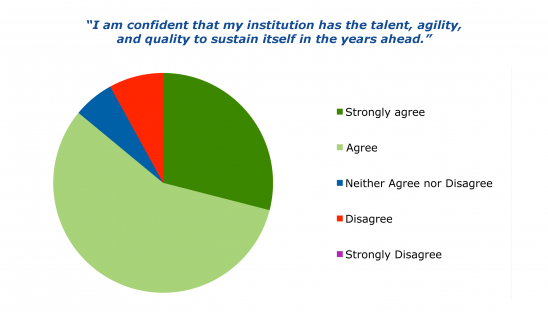

The presidents praised their own academic communities for having the wherewithal to succeed in the years ahead. Complacency, they know, is simply not an option. Several presidents highlighted demographic changes. Only a tiny minority of the presidents (less than 10%) lacked confidence in their own institution’s “talent, agility, and quality.” One lamented that many institutions “are not prepared to provide a truly inclusive culture for the majority of college-going students in future years (namely, students of color).” Another argued that “New England has excess capacity in institutions of higher education and our demographics (declining population of high school graduates) are the worst in the country. Tuition-dependent institutions must either diversify their revenue streams and/or expand their markets—at a time when everyone is trying to do the same thing. I do not believe all will be successful, and while the very wealthy colleges will continue to survive more or less as they are, the others must change their business model or die.”

Only 9% of respondents agreed that “many of the new ideas about alternative revenue streams … would be contrary to our mission and values.” One president stressed how “my campus relies heavily on profits from nontraditional students in online and campus-based degree and professional programs. I don’t see how small tuition-driven campuses can survive without alternative revenue streams.” The risks of obliterating the more intimate college experience have not been as well-articulated as their runaway costs. “For small colleges to survive into the future,” one said, “they must clearly articulate and prove the value of an on-campus experience.” The hoopla about MOOCs presents a golden opportunity to counter with a defense of the holistic benefits of a traditional campus.5

But defending the virtues of campus life cannot be coupled with resistance to change. One president argued, “Smaller private colleges, many of them surviving with unsustainable tuition discounts [internally funded scholarships], not only need to leverage digital technology to reach new audiences, they need to use that technology in a different financial model that is less costly to students, more customized to the students and more efficient for the college.”

Those that hit a financial wall will, according to 60% of the presidents, “be absorbed by other institutions or shuttered.” The stakes are high. Many New England presidents believe there will be a shakeout in the years ahead. Their confidence for their own school doesn’t extend to their neighboring institutions nor to New England generally. Only 57% of these presidents agreed that, “The small New England college will remain an important fixture within the academic landscape for many years to come.” Put bluntly by one respondent: “If your institution does not have a well-defined market niche … that is robust, be that market in or out of New England, it is toast.”6

Anticipating a new model

Is New England’s historic academic leadership at risk? Is its diversity of institutions an essential feature in the strength of that leadership worth preserving? What value do these institutions have in defining the unique character of this region? How can they fundamentally restructure themselves to ensure their survival?

New England is characterized not only by its major brand-name schools, but also by its mosaic of different types of institutions serving multiple populations and purposes. These smaller schools play a significant role in creating and sustaining the academic identity of this region. But we cannot preserve them as museum pieces. Every institution needs a sustainable financial model that addresses contemporary challenges. Perhaps we need an environmental impact analysis not only of the economic benefits of our numerous schools, but also of their even less tangible social and cultural importance, which will be a tough sell for those skeptics impatient with escalating costs in higher education. We also need to better understand the interplay of large and small institutions within New England—and the few degrees of separation among them. And we need to better explore potential interdependence among small schools and practical opportunities for collaboration, alliances, resource-sharing and outsourcing. A persistent theme we heard was the need for “new models”—and it will be telling to see whether the leadership of smaller institutions has the agility and clout within academe to generate new ways of doing business, and whether there is enough time to demonstrate what they can do in the realm of innovation.

With a pragmatic idealism about the value of their schools, and a faith in the caliber of their faculty, New England’s college presidents face an unsettling future where they will need to articulate their case to a concerned public, and find new ways of balancing costs with income, as they lead in the process of changing often tradition-bound, resource-constrained, but immensely vital institutions.

Jay A. Halfond is former dean of Boston University’s Metropolitan College, currently on sabbatical (serving as the Wiley Deltak Faculty Fellow) before returning as a full-time faculty member at BU. Peter Stokes was recently appointed as vice president for Global Strategy and Business Development at Northeastern University after many years at Eduventures.

1. This survey was conducted July 2013, with the sponsorship of the New England Journal of Higher Education. Thirty-five of 150 area presidents responded both to the 10-question survey (on a 1-5 scale) and to the request for open-ended, anonymous comments. The authors thank Abigail McMurray for her invaluable work in administering this survey.↩

2. Some of the more thoughtful recent journalistic pieces include “The Reinvention of College” by Laura Pappano in the Christian Science Monitor (June 3, 2013, pp. 26-32), “The Attack of the MOOCs” in the Economist (July 20, 2013, pp. 55-56), “College is Dead. Long Live College!” by Amanda Ripley in Time Magazine (October 29, 2012, pp. 33-41), and “The End of the University as We Know It” by Nathan Harden in the American Interest (April 8, 2013). But fantasies on the future of higher education have existed since the early dawn of online education: for example, “The McDonaldization of Higher Education: A Fable,” by Jay A. Halfond and David P. Boyd, in the International Journal of Value-Based Management, 1997, 10: pp. 207-212. A more current, cautious note was struck by Richard C. Chait and Zachary First, in “Bullish on Private Colleges” (in Harvard Magazine, December 2011, pp. 34-39).↩

3. A recent Gallop survey reported in Inside Higher Ed (May 2, 2013) found America’s college presidents did not view MOOCs as a panacea for any of academe’s ills. On the other hand, the 2013 Survey of College and University Business Officers conducted by Inside Higher Ed and Gallup showed that less than half agreed that their business model would be sustainable in the coming 10 years. And only 13% believed that reports of colleges facing a financial crisis were overblown.↩

4. A recent dire forecast by Jon Marcus appeared in the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine on April 14, 2013, pp. 27-29: “Are Some Massachusetts Colleges on the Road to Ruin?”↩

5. An op-ed piece by James McCarthy, president of Suffolk University, disaggregated the likely impact of educational technology and MOOCs on different types of academic institutions (in the Boston Globe, July 27, 2013, p. A9).↩

6. Diversification has its own rewards and commoditization its dangers. See “Vive Les Differences: How Commoditization Challenges Higher Education Diversity” by Jay Halfond in EvoLLLution, June 13, 2013. According to the “2012-2013 Almanac” of the Chronicle of Higher Education (August 31, 2012, p. 20), only 6.4% of the nation’s 4,634 colleges and universities fall within the Carnegie Classification as “Research Institutions.” While most others are community and public four-year colleges, 19.1% others are “special-focused” (faith-based, professional, etc.) and 11.3% are private, non-profit baccalaureate colleges.↩

[ssba]