Presidents, trustees and senior administrators at New England colleges and universities all feel the pressures: keep tuition down, be competitive academically and make sure the physical campus draws talent from a shrinking pool of traditional high school graduates and new nontraditional students. Given resource limitations, something’s got to give and, for many campuses, investment in facilities is the first to get cut.

Presidents, trustees and senior administrators at New England colleges and universities all feel the pressures: keep tuition down, be competitive academically and make sure the physical campus draws talent from a shrinking pool of traditional high school graduates and new nontraditional students. Given resource limitations, something’s got to give and, for many campuses, investment in facilities is the first to get cut.

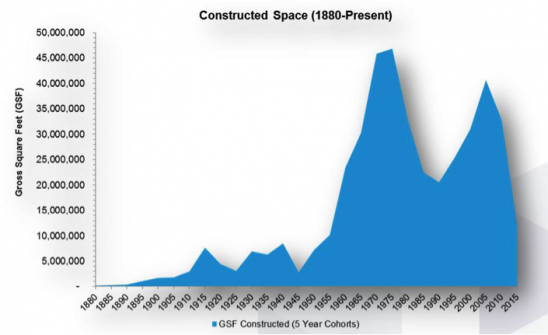

The problem is that we are entering an unprecedented period when two historic waves of building construction demand capital renewal investments even as resources available for capital are limited by reductions in state funding, decreases in research and philanthropy and debt limits set by trustees. New England campuses built more space from 1960 to 1975 than over the previous 80 years combined. Then many campuses followed with a second construction boom from 1995 until the Great Recession slowed building.

Now, faced with having to do “catch-up” renovation on the first wave of buildings that are reaching 50 years old and “keep-up” or stewardship on the second wave of buildings, campus administrators are finding there is just not enough money to do both. It is starting to show to even the casual observer.

This facilities challenge also comes at a time when the pool of traditional high school students is shrinking, at least for the remainder of the decade. Competition for these students is heightened, making the need for modern facilities more important than ever. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, every New England state will experience a decline in the number of high school graduates at least until 2020. Student attention on campus facilities is evident in social media commentary about the subject; for example, Classrooms of Shame on Tumblr where students and faculty post pictures of rundown, dirty and poorly maintained classrooms (“Classrooms of Shame,” Inside Higher Education, Nov. 12, 2013, and “Students, Professors Highlight Classrooms of Shame,” USA Today, Nov. 23, 2013).

Finally, the growth of online learning becomes another factor in the physical campus management equation. According to the Sloan Consortium, online learning enrollment has increased by over 9% annually since 2003 (“Trends in Online Learning,”Elaine Allen and Jeff Seaman, Sloan Consortium, 2013). Harvard professors Clayton Christensen and Michael Horn call the growth of online learning “disruptive innovation” that will challenge the physical campus and change face-to-face learning (“Online Education as an Agent of Transformation,” New York Times, Nov. 1, 2013).

This article provides a perspective on the physical condition of New England’s colleges and universities using data from Sightlines, a higher education facilities consulting firm in Guilford, Conn. It will also provide perspectives from leaders at New England campuses on what can be done to address facilities challenges now and in the future.

State of facilities at New England campuses

In 1988, a survey by Coopers & Lybrand for APPA, the group representing leaders in educational facilities, and the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) estimated $20 billion in deferred maintenance at the nations’ colleges and universities (New York Times, “Campus Buildings Are Decaying, Survey Says,” Oct. 18, 1988).

Almost 25 years later, The Chronicle of Higher Education published an article, “How the Campus Crumbles”(May 20, 2012) with the conclusion: “that deferred maintenance on college campuses amounts to about $36 billion across the country …”

How could we have spent billions of dollars on new construction and renovation over the past 25 years and still see a doubling of the amount of deferred maintenance? Sightlines examined data collected and verified at more than 100 New England institutions to answer that question. (This data was initially presented at the New England board of Higher Education’s Summit on Costs in Higher Education, Oct, 21, 2013.)

We looked at four major indicators:

Age profile

The age distribution of space on a campus is important to know and what can be done to change it to reduce risk of building failure.

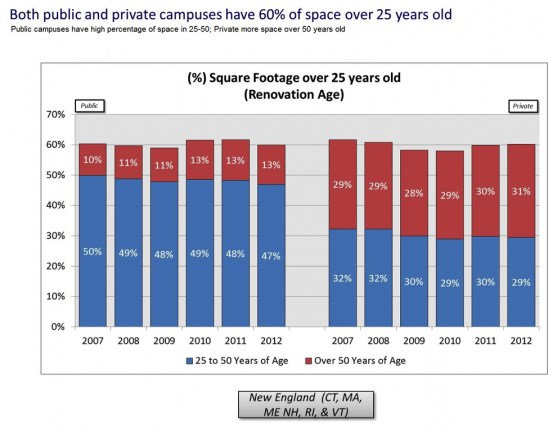

Despite the addition of new modern buildings, campuses of all kinds continue to have a high percentage of buildings that are over 25 years old—an age when life cycles of key building components like roofs, windows, doors, HVAC, electrical and plumbing systems begin to come due for replacement.

From 2007 to 2012, New England campuses saw virtually no change in the total percent of space over 25 years old.

An interesting difference is that public institutions have more than 50% less space that is over 50 years old than do private campuses. While that might appear to be a strategic advantage, Sightlines has found that having too much space in a single age category (nearly 50% of public campuses space is 25 to 50 years old) can be a disadvantage because so many building component life cycles come due at the same time. In addition, private campuses tend to have a significant proportion of building space constructed prior to 1951 and after 1991—eras when buildings were more durable and likely to last longer if properly maintained,

Capital investments

How much capital are institutions investing in existing facilities and how is the source of those investments changing?

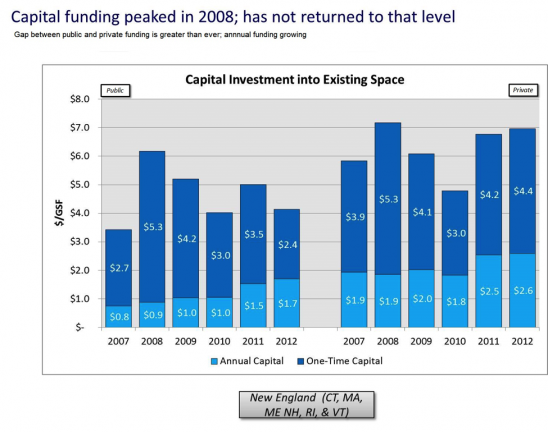

Capital investment in existing space at New England campuses peaked in 2008 and has not recovered to those levels. Public campuses have been hit particularly hard by state funding cuts due to the recession.

Both public and private campuses are relying much more on annual capital institutional funding than on one-time capital coming from state capital funds (in the case of public institutions), gifts or bonding. Despite the recession, institutional capital funding more than doubled at public institutions and increased by 37% at private campuses that already had a high level of annual investment.

The gap between total capital investments at public vs. private campuses was greater in 2012 than in any year Sightlines has tracked these numbers. In 2012, private New England campuses invested $7.00/square foot compared with $4.10/square foot at public institutions. While public institutions have always had a large tuition price advantage over private institutions, there is a high likelihood that without major capital infusions, these campuses will deteriorate faster and, as a result, be less attractive to students.

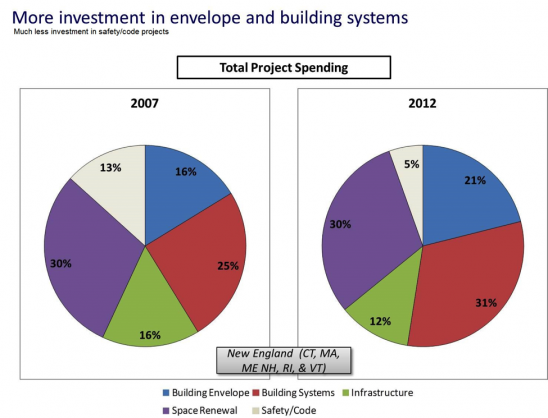

Capital projects allocation

Sightlines has also collected data on how capital investments are being spent. We found a significant shift to spending on building envelopes (roofs, windows, exterior) and building systems from 2007 to 2012. This is another sign that deferred maintenance is getting to critical levels at New England campuses.

Project backlogs

How does the current state of deferred maintenance backlogs drive investment decisions?

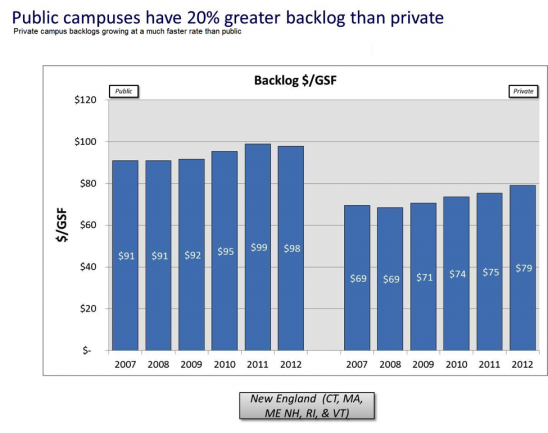

Sightlines data shows a significant growth at both public and private campuses in the overall project backlog. Mirroring the differences in capital investment, public campuses have a backlog that exceeds private institutions by almost $20/gross square foot—about a 20% difference. At an average 2.5 million-square-foot campus, the difference would amount to $50 million.

Most experts believe when the backlog reaches $100/gross square foot, campuses can no longer act proactively to maintain the campus. They become almost totally reactive to repair needs and emergency calls to fix building reliability problems.

Whether we are looking at public or private campuses, the conclusion is the same: The impacts of the two historic waves of construction are taking their toll on campuses. The buildings continue to age faster than they can be renovated. And this is happening at a time when capital funding, especially for the public campuses, has contracted.

Case Studies: What Can Be Done to Reverse The Trends Affecting the Physical Campus?

Sightlines interviewed senior administrators at three New England campuses that are addressing the challenges to the physical campus using a combination of these strategies:

- Aggressive enrollment management practices to expand the pool of prospective students and embrace online learning.

- Documenting existing deferred maintenance backlogs and projecting future needs coming due.

- Balancing capital investments in new vs. existing space and making sure space is being used properly.

- Creating portfolios of capital investment to set clear priorities and determine whether to renovate, repurpose, replace or demolish aging buildings.

Here are their stories.

University of Massachusetts Amherst

The University of Massachusetts Amherst, the public flagship university in the Commonwealth, has more than 27,000 students and more than 11 million gross square feet of space within 330 buildings. The campus leadership started documenting the project backlog in 2006 and found that the numbers were staggering—almost $2 billion.

Juanita Holler, UMass associate vice chancellor for facilities and campus services, realized that the university needed to approach the deferred maintenance backlog is a fundamentally different way: Simply qualifying the large backlog would not be enough to convince university leadership that a major infusion of capital was critical. Finance and facilities leaders needed to develop a clear, multi-year capital strategy, set priorities and advocate for resources to fund them. Some buildings would need to be demolished, a fact that needed to be made clear to senior leaders. (Business Officer, “Flagship Focuses on Failing Facilities,” January 2013).

UMass created a set of capital investment portfolios for the campus that included placing building in categories like maintain, renovate, repurpose and transition (i.e. slate for demolition). The portfolio strategy helped set clear priorities for investment and made sure that large investments were not made in buildings slated for repurposing or demolition. The approach also provided a way to track impact of funding.

The project backlog has been reduced by over $350 million since 2009. Projects that deal with building envelope, building systems and utility infrastructure have been given a higher priority. The aging central heating was replaced by a modern cogeneration plant and utility consumption and costs have declined dramatically. UMass has placed a priority on eliminating buildings that are in poor condition and not heavily used on campus. Since 2007, more than 30 buildings, comprising over 150,000 gross square feet, have been demolished in order to reduce the deferred maintenance burden. Some of these buildings, such as the campus power plant, have been replaced with modern, more efficient facilities. The result is less deferred maintenance and lower operating costs.

University of Maine

The University of Maine in Orono has one of the highest percentages of campus space that is over 50 years old and not renovated. In 2013, the campus has 44% of space over 50 years old, almost double the peer average. President Paul Ferguson has set in place “The Blue Sky Plan,” which includes aggressive enrollment management and a multi-year capital strategy to address the needs of aging buildings, renew physical space in core mission programs and steward buildings in good condition to reduce the rate of deterioration.

Janet Waldron, senior vice president for administration and finance, says UMaine’s strategy for meeting the facilities challenges requires the coordination of multiple plans. “We are tying the campus master plan to our strategic enrollment plan,” she said. “We are documenting our backlog of deferred maintenance and developing a multi-year capital plan to provide funding to improve the net asset value of our buildings. We are making sure our campus facilities operations improve their productivity and efficiency. No single strategy will work when the problems are this big.”

UMaine’s aging facilities present a special challenge for online learning and the technology support required. Renovation work must incorporate the latest technology in both classroom and residential facilities: “Many of the online credits hours are completed by our resident students in their dorms. We need the technology infrastructure in those buildings to support their learning,” said Waldron. An out-of-date dormitory, Estabrooke Hall, has been repurposed to become office space and a technology-rich learning center.

The plan is already producing results. New first-year freshman enrollment has increased by an average of 10% each of the last two years. In November 2013, the Maine voters approved a $15.5 million bond for laboratory and classroom upgrades at UMaine campuses. Fundraising is underway to enlist donors to provide capital gifts to implement the Blue Sky Plan projects. And the university has increased its commitment of annual capital funds to address facility needs.

University of Hartford

The University of Hartford is a private comprehensive university with 7,000 students, and 2.2 million gross square feet. Over 50% of the 60 buildings on campus were built between 1951 and 1975. The campus has grown in the past decade while enrollment has stabilized. Capital investment resources have been limited and the backlog of deferred maintenance is growing.

The university leadership realized that a comprehensive strategy needed to be implemented to document facility needs, utilization of space and the annual costs of operating the campus. Norm Young, the university’s associate vice president for facilities planning and management, outlined the plan: “We started by documenting the deferred maintenance needs and categorized those needs as building investment portfolios. This helped us optimize the impact of investments and focus on critical building systems and strategic priorities. Then we documented the utilization, configuration and quality of our learning spaces to better align instructional needs with available space. And recently we quantified the annual cost of operation by building to understand the full program operating and capital costs.”

As a result, the campus is developing a five-year strategic capital plan that balances investment in building envelope and mechanical systems, utility infrastructure and classroom space. Critical building reliability problems have received top priority. The space utilization analysis found that the the campus had more large classrooms (over 30-student capacity) and fewer small classrooms than needed to accommodate the current course enrollment. As a result, the campus is tying together restructuring of classroom space and renovations into a comprehensive strategy for space renewal.

Assessing opportunities to reduce facilities operating costs has also paid dividends. Utility costs have been reduced by 17% and the campus has shifted to doing more preventive maintenance work and, as a result, fewer reactive work orders.

“Our capital investment and facilities management strategies needed to be data-driven, flexible and clearly communicated through a comprehensive plan based on institutional priorities,” said Young.

Managing the future

There is no doubt the challenge of growing deferred maintenance, declining enrollment and adjusting to online learning will require leaders at New England campuses to think very differently about their physical campuses. Traditional models of capital investment will no longer work. There will not be enough money to fix all buildings, so priorities will need to be set and some buildings will need to be demolished, repurposed or replaced.

The stories provided by these campuses should encourage all campus leadership that there are strategies that work if administrators and trustees have solid data to understand their campus data and trends; use the data to implement a systematic plan to for capital investment; and communicate with all constituents the difficult decisions that need to be made to manage their physical campus in the future.

James A. Kadamus is vice president of Guilford, Conn.-based Sightlines.

[ssba]