Higher education has provided New England with an economic advantage, as the region without strong natural resource advantages has relied on its higher education institutions (HEIs) and brainpower. A higher education-based economic advantage has enabled the region to develop strong well-paying technology and knowledge-based industries tied to New England’s academic research and development (R&D) capabilities, and to lead the nation in per-capita income (currently 30% above the national average) and unemployment consistently below the national rate.

Higher education has provided New England with an economic advantage, as the region without strong natural resource advantages has relied on its higher education institutions (HEIs) and brainpower. A higher education-based economic advantage has enabled the region to develop strong well-paying technology and knowledge-based industries tied to New England’s academic research and development (R&D) capabilities, and to lead the nation in per-capita income (currently 30% above the national average) and unemployment consistently below the national rate.

Lumina Foundation’s report A Stronger Nation suggests that about two-thirds of working-age adults in New England will require education beyond high school by 2025, while the region’s postsecondary attainment is currently below one-half. This gap is affecting regional growth. New England lags behind other regions, and increasing numbers of national and regional employers look to other regions to grow employment.

New England would benefit if colleges and universities enabled more of an employability (E) advantage for the region. Broadly enhancing the employability of residents by expanding access to advanced education, particularly education aligned with areas in which there are long-term skill gaps, can also lead to well-paying careers for greater numbers of people and help arrest rising income and geography-based inequality in the region.

Clusters

Many New England industry clusters built over the past century have strong ties to higher education. These include an array of technology- and education-based industries, where employment concentration is 40% above the national average. The high-technology clusters of note include aerospace, defense, biotech and information technology. An export sector that is increasingly R&D-based is healthcare, tied to biotech and pharmaceutical industries; healthcare’s concentration in the region is 25% above the national average.

While these clusters remain strong in New England, other nations and U.S. regions are gaining ground on New England. Since 2000, high-technology industry employment as a percentage of total employment has declined in New England from 7% to 6.6%, while holding constant in the U.S. Manufacturing employment concentration has experienced a particularly steep decline in New England, dropping from 13.4% and above the U.S. average concentration, to 8.3% of total employment and below the national average.

While high energy costs and other business factors may contribute to technology and knowledge-based industry decline, labor skill shortages and demography are working against the economic vitality and competitiveness of the region now—and will increasingly do so if efforts are not made to close the gaps.

New England’s regional unemployment rate has been consistently below the U.S. average, as the region’s population and labor force have been growing at only about half the U.S. average since 2000. Along with this slow growth, the population is aging across New England, with the percentage of the population who are young adults (ages 25 to 44) going from over 31% (and above the U.S. average) to 25% (and below the U.S. average). Meanwhile, the share of the population age 65 and older went up from below 13%, to greater than 16%. This highlights the need for New England HEIs to work together to help ensure that the demography does not work strongly against the regional economy. One way to accomplish this is by focusing education in the region more purposively and directly on employability needs and expanding access to advanced education aligned with economic opportunity.

T-shaped challenge

Employability needs are broad and deep. They are so called T-shaped, including wide breadth and, at the same time, specialized skills. This means strong liberal arts/humanities education is critical along with strong career and technical skills, as well as skills-based education and experience, including internships and work-based learning. And New England higher education is well-positioned to do this, especially if its broad range of excellent institutions–research universities, public flagships and regionals, liberal arts colleges, and community colleges–can work together and with industry to help students align their academic program choice and extra-curricular activities with career planning. New England higher ed could then provide intentional, and more seamless education/career pathways to New England employment. This would involve providing current and forecast information about occupations and career opportunities, integrated academic and career guidance and planning, robust articulation and transfer of credits from secondary to postsecondary education and within postsecondary (including from community colleges to leading R&D HEIs), and internships and work-study experiences that strongly connect New England college students to employment in New England.

Working against the region’s economic vitality, however, is the Two New Englands paradox. Strong economic conditions and industry and employment benefits from higher ed are concentrated within the region where higher ed R&D is concentrated, including Boston/Cambridge-128, Providence, Hanover/Lebanon and New Haven. R&D from Yale, Dartmouth, MIT, Harvard and Brown has contributed to economic growth globally, but not in rural parts of New England. Most of the R&D-leading HEIs are concentrated in urban areas (with notable exceptions being Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H, and the UMass flagship in Amherst, Mass.), while most rural areas in the region are left without many of higher education’s economic advantages beyond the direct spending by the locally based institutions and their students.

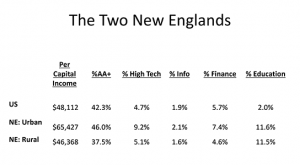

The Two New Englands underscores a significant gap between urban and rural New England. Urban New England is well above the national average in per-capita income, educational attainment (% of adults with associate degrees or higher) and employment concentration in high tech, information and finance. Rural New England, however, is below the national average on all of these. (See table: The Two New Englands). This is true while the concentration of employment in all areas of education is equal in rural and urban New England—and significantly higher than the national average. So it is not for lack of educational institutions that rural areas lag behind urban areas.

New England would benefit if HEIs across the region focused more on employability of graduates for jobs in the region, and committed to a regionwide collaboration to address labor market skill gaps. This could help ensure that rural areas do not fall further behind. Employers that might not stay or be attracted to New England because of high costs could locate in the region’s rural areas if an appropriately skilled labor force were there, thus benefiting from New England’s higher ed and tech advantages while avoiding the high costs of urban areas. This could be particularly attractive for larger employers that are based in urban New England, but looking to expand employment nearby.

What can be done?

A first step has already been taken with NEBHE’s organization of the New England Commission on Higher Education & Employability, chaired by Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo. The Commission comprises representatives from all sectors of higher education in all New England states, along with regional employers and public officials. The Commission’s purpose is to inspire and enable a regional approach to employability that builds on the region’s higher education advantage. Preliminary priorities that have emerged include:

- Having HEIs in New England commit to collaboration on employability. They could, for example, share a goal to increase college attainment in the region (associate degrees or higher) from the current 46% to over 60% by 2025, and align education programs to regional employment opportunity.

- Strengthening HEI “cross-sector” (Research, Regional, Private, Community College) collaboration, with a focus on student educational pathways to employment in the region. This could involve stronger articulation and transfer programs for students in the region between community colleges and public and private research universities in STEM and other high-demand program areas. This would target community college students most interested in advancing their education beyond the associate degree, particularly those concerned about costs and facing geographic restrictions during their first years of college.

- Enhancement and promotion of sub-bachelor’s degree options, including industry and occupation certificates and career and technical education, aligned with labor market needs and well-paying careers, and focused on areas with high skill gaps and high job availability.

- Strengthening academic preparation and academic and career planning for students in K-12. This could include making available to students and their families “state of the art” labor market information and career-planning tools in New England’s secondary and postsecondary institutions. Partnerships with industry could be extended and advanced to include more work-based learning opportunities for students in the region, such as internships, co-ops and work-study programs. Best practices could be modeled in career preparation and academic program alignment.

- Coordination of re-education and retraining efforts for adults in a regionwide collaboration focused on needs of employers in strong clusters that are pervasive in the region. This could include a regionwide effort to provide credit for prior learning experience. Innovative and coordinated practices could enable adults to retrain or be placed in well-paying employment across the region.

- Focus on efforts that address income inequality based on economic opportunity gaps and underrepresentation of various groups in the region’s competitive industries. Explicit equity objectives and practices could support advancement of underrepresented groups.

- Rural HEIs should be included in regionwide efforts and have opportunity to partner with R&D focused HEIs. This could involve expanding innovative pedagogy using technology and varied course delivery (e.g., hybrids and virtual) to connect urban and rural institutions and advance higher education services in rural areas.

- Link employability efforts to R&D advantages, for example, by leveraging of R&D to promote the locating of production/manufacturing rural areas.

And do all the above in ways that distinguish the region as a national and global leader in R&D … and E.

Ross Gittell is chancellor of the Community College System of New Hampshire, vice president and forecast manager of New England Economic Partnership, and a co-chair of NEBHE’s Commission on Higher Education & Employability. His work has been published frequently in NEJHE.

[ssba]