“When both of the partners meet our standards for excellence in teaching and research, and where they can both make contributions to the curriculum, it’s a great way to both recruit and retain. … It also brings us the greater richness of what two people bring.”—Cristle Collins Judd, Dean for Academic Affairs, Bowdoin College

“When both of the partners meet our standards for excellence in teaching and research, and where they can both make contributions to the curriculum, it’s a great way to both recruit and retain. … It also brings us the greater richness of what two people bring.”—Cristle Collins Judd, Dean for Academic Affairs, Bowdoin College

Though Dean Judd is referring to faculty couples, she could be speaking about any dual-career couple recruited to a college or university. Our institutions want to bring the best talent we can onto campus. Increasingly, that means anticipating and responding to the needs of the spouse or partner in the recruiting process.

Recent research from Stanford University and the University of Virginia supports the experiences many of us have had: Job opportunities for the partners of recruited faculty are key to successful recruitment and retention. As the provost at a Midwestern research university put it, “The main reason they say no is because their spouse can’t find a good job here. And the main reason they leave is because their spouse never found a good job here.”

What can we do to maximize our institutions’ return on the resources invested in faculty recruitment? One possibility is establishing a dual-career couples support program. According to the International Higher Education Dual-Career Association (formerly the Higher Education Dual-Career Network), more than 50 colleges and universities in the U.S. and abroad have some level of staffed initiatives ranging from printed materials and simple websites to extensive job support assistance for partners.

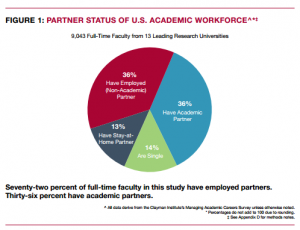

Most faculty have spouses employed outside the home

Nationally, dual-career couples are common in higher education. A survey by Stanford University’s Clayman Institute indicated that 72% of the full-time faculty at the U.S. research universities have partners working outside the home. Those working partners are equally divided between academia and other industries. Of the faculty surveyed, 10% were brought on in their position as a “dual hire” with their partner.

For institutions trying to diversify their faculty, the research confirmed that women are more likely to refuse a job offer because of their partner’s lack of appropriate job opportunities in the area. This issue can be even more pronounced for women in the natural sciences of whom 83% reported being partnered with another academic scientist (versus 54% of their male peers). This “disciplinary endogamy” creates another layer of complexity to hiring efforts. The University of Virginia study conducted in 2010 looked at recruited faculty who rejected the institution’s offer for a tenure track position from 2006 to 2009. The researchers found dual-career issues to be the foremost concern for the respondents. This was particularly true for underrepresented minorities (83%) more so than whites (53%).

These results suggest that addressing the work needs of the “accompanying partner” may be critical to the successful recruitment of the top talent, particularly women and minority faculty.

Establishing a support program for dual-career couples

Several years ago, researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Education tallied a “back of the napkin” estimate on the cost of recruiting a professor at $96,000. Around that time, the University of Wisconsin-Madison estimated that it was spending an astonishing $1.2 million across all disciplines to replace a faculty member. No matter which figure is used, faculty hiring takes significant resources. In addition to the bottom-line impact, there are myriad benefits of retaining professors at all stages of the tenure track, including recouping start-up outlays, generating grants, fostering research collaborations and boosting department morale. This last benefit, while less tangible, is important. Dual-career couples support staff often hear from faculty: “Why weren’t you around when [my spouse and I] were moving?” The development of this kind of resource resonates very positively with stakeholders throughout the campus.

Compare those dollar-figures with the potential expense of increasing the support for dual-career couples on your campus. The budget for dual-career couples support typically consists of a part-time staff member, office, computer, phone and publications. The truth is that most campuses are already offering job search assistance to recruits and new hires, but perhaps by word-of-mouth that may not reach all the potential beneficiaries such as recruits, new faculty, deans, provosts and search committees. By appointing a “gatekeeper,” the institution’s academic and administrative areas share a single source of useful, current information.

An entry point and clearinghouse for information

The staff member acts as an entry point to a web of services and contacts on and off campus. Services can include: resume and cover letter review, interviewing practice and networking support. Contacts usually involved provosts’ and deans’ offices, academic department chairs, and human resources and career services. Importantly, faculty who have used dual-career couples services themselves are usually wonderful resources.

The dual-career staff person should extend the support already being offered by the hiring department in several ways:

- Offering in-house expertise. If the partner is an academic, arranging a meeting with the department chair in their discipline for an informational chat can go a long way. This is usually done by the academic department head. However, if the partner is not an academic, but works in higher education currently or has transferable skills, introducing him or her to a senior staff member in a relevant department is an easy and valuable benefit to offer. At a minimum, the introduction helps provide a warm welcome and recognizes the important role the spouse plays in the recruitment process. It also benefits the department by: providing another opportunity to set expectations of what the institution can and cannot do for partners; defining and limiting the time commitments for everyone involved; and gathering helpful information about candidates’ needs (e.g., childcare and relocation issues).

- Sharing information on local job resources. In addition to job boards like Monster.com and indeed.com, there are more specific ways to find new opportunities in a region. The New England Higher Education Recruitment Consortium (NEHERC), a partner of the New England Board of Higher Education, works to support dual-career couples and to diversify the faculty and senior staff at 70+ member institutions. NEHERC aggregates all faculty, staff and research openings at www.neherc.org, a free job board with typically about 3,000 positions posted. (Information on joining the NEHERC can also be found on its website.) A recently relocated spouse used NEHERC, college and university websites, higheredjobs.com, Facebook and LinkedIn to help her conduct a remote job search in Boston. A good dual-career support program can share ideas quickly between recruits and new hires to enable them to gather good information.

- Connecting recruits and new faculty with peers. If faculty in the hiring department are of similar age or life stage as the potential hire, it may be natural to make a connection to share experiences about relocation and off-campus life. Often, however, new faculty hires are few and far between. Helping the search committee chair find another recently relocated faculty spouse with whom the partner can speak provides a valuable resource and community link. Conversations with other spouses allow the accompanying partner to ask questions they might hesitate to pose with search committee members about transitioning to a new environment, difficulty of a job search in the area and quality of schools. Faculty families who used the dual-career couples support program in the past are usually a great, and eager, pool of volunteers for this role.

A “back of the napkin” estimate

Depending on the types of services offered and level of involvement with search committees, a dual-career couples program can be run on as little as 10 hours per week by a program manager in the office of the provost, dean or human resources. Determining and maintaining information about services offered, regional and online job search supports and engaging with various stakeholders are the key responsibilities. The staff person needs office space, a computer and basic office supplies as well.

Finally, program evaluation can include: Return-on-investment analysis focusing on financial results (reduced recruitment costs and grants received by dual-career faculty who used services); productivity (see J. Woolstenhulme’s working paper 2012); and “customer satisfaction” (use of program by recruits and new faculty, search committee feedback).

Laurel Sgan Kibel is program coordinator with the New England Higher Education Recruitment Consortium and the former dual-career couples support manager at Washington University in Saint Louis.

For more on dual-career couples in higher education:

Higher Education Dual-career Network An international association of colleges, universities and affiliated institutions which have dual-career couples programs.

The Dual-Career Mojo that Makes Couples Thrive by Monique Valcour, Harvard Business Review blog, 2013.

On the Cutting Edge: A NAGT Professional Development Program for Geoscience Faculty A source of articles, profiles and other information for all dual-career academic couples, not only in geosciences.

Related Posts:

Academic Couples (Book Review)

[ssba]