Higher ed has always operated in a very cyclical nature. If we look at historical movements on college campuses, including protests in favor of desegregation in the 1960s, higher ed has always been far more reactionary than proactive. For example, following the protest at the University of Missouri (Mizzou) in 2015, thousands of students at colleges and universities across the U.S protested in solidarity with the students at Mizzou. Their efforts were met with widespread participation from their student body, and undoubtedly the ear of administration. However, like every student action in higher education—especially when these movements carry such strong voices of marginalized groups—most administrators moved on once summer came and once students became alumni.

Higher ed has always operated in a very cyclical nature. If we look at historical movements on college campuses, including protests in favor of desegregation in the 1960s, higher ed has always been far more reactionary than proactive. For example, following the protest at the University of Missouri (Mizzou) in 2015, thousands of students at colleges and universities across the U.S protested in solidarity with the students at Mizzou. Their efforts were met with widespread participation from their student body, and undoubtedly the ear of administration. However, like every student action in higher education—especially when these movements carry such strong voices of marginalized groups—most administrators moved on once summer came and once students became alumni.

This is to say that higher ed cannot keep its promises, especially when that promise is to BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) students.

Last year, even as the world was shaken with a global health pandemic, and colleges and universities were forced to develop sustainable programs for distance learning, BIPOC students, and arguably everyone, experienced another pandemic: the inhumane and cruel loss of Black lives.

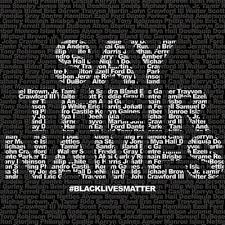

It should not go unnoticed that as the world experienced so much loss from COVID-19, BIPOC people were experiencing a very grey world. I recall reading about the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Donald Ward, Phillip Jackson and the countless other lives lost to police brutality. As the eyes of the world opened to police brutality, no doubt made more clear by the isolation of the pandemic, BIPOC students were forced to experience a second pandemic as spectacles to onlooking eyes.

Grief became performative, and performing this grief became a determinant of how “woke” an individual was. People would post Black boxes to show their support of the movement, reposting traumatic videos of people dying as a way of showing how “educated about the movement” a person was, and for institutions, how woke they were by drafting a politically correct response to these senseless deaths and pledging to establish an “antiracist” campus. But can any institution say they actually did this?

In fact, some universities fall back on the idea of free speech, academic freedom and the protections of tenure as the reason that even the most bigoted professors are still safe within the solid structure of college campuses. I’m not saying you can teach people how to be consistently antiracist. I’m saying that being committed to antiracism is inherently fostering a space where all students can feel welcomed. And establishing practices and policies can support those previously and currently excluded and oppressed from institutions of higher education. The hard part for an institution is committing to these same values in every aspect of its work. I think if anyone digs deep enough, they’ll find that very few schools have done substantive work to fulfill these promises for establishing antiracist campuses, and those that did start this work did so before too many Black Lives were lost.

The problem with making false promises, aside from the obvious disappointment from those who would benefit, is that so many people had to die for that promise to be made, and too many institutions can’t bother to actualize it.

Earlier, I said that higher ed has always operated in a cyclical manner and this is why: Higher ed has always operated as if a new year, a new academic term and full leaves meant that the problems of the past year had been absolved. It is almost as if institutions question: Why should higher ed remember all the trauma of the past year? Wouldn’t it be best to move on? It is almost as if the closing of one fiscal year means the end of one show and the start of another. But should that be the case?

BIPOC students still wear the shadow of these deaths like a shield of armor, constantly carrying the grief of Black people as a reminder to always be on guard. We live in a world where so many spaces are predominantly white, and higher ed, as we know, is no different. For a second, can we imagine how these spaces can often not only isolate Black students, but also make them feel as if they need to be on guard? So now, when the world is watching Black grief on news clips, on social media and in the headlines, and campuses push their “antiracist” initiatives to the forefront of media, can we imagine how the false promises that institutions make are like tallies going against the entire system of academia.

One university promises reform through DEI training, and another promises to establish an “antiracist” campus” and yet, here we are, in many ways, sitting in the same place higher ed has been for many decades. The disappointment, the lack of follow-through—it almost cancels out the efforts of so many institutions that are actually doing substantial work to establish campuses that are inherently race-conscious, like Boston University’s Center on Antiracist Research, or the University of Denver and its work on inclusive excellence that predates the horrific killings of this past year.

This time, higher education should not be able to forget; institutions need to be reminded to say their names—all of their names. And we—myself included—need to hold institutions accountable for the promises they made last spring. Remind them that their students, faculty, staff and administrators are not exempt from doing the hard work, their BIPOC students do matter just as much as the lives that have been lost. We must hold higher education accountable for reopening without relapsing into the same cyclical pattern of forgetting the pain and trauma of BIPOC students.

For once, higher education (the academy, it’s administrators, etc.) must take responsibility for doing the work to transform higher education into an environment that inherently fosters an inclusive, equitable and safe environment for BIPOC students, staff and faculty. And FYI, the current practices are not working. It’s time to go back to the drawing board! Move past the performative promises of last spring, and move onward into making real systemic change. Do not let these lives lost be in vain.

Sara Jean-Francois is assistant director of NEBHE’s Regional Student Program, Tuition Break. She recently earned her master’s degree in public policy from Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management, where she conducted significant research on race-conscious campuses and issues of equity and inclusion in higher education.

[ssba]