Nearly 50 years after the landmark legislation aimed to open higher education to all Americans, colleges and students face a new set of threats …

The Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA) was signed into law on Nov. 8, 1965 to strengthen the educational resources of our colleges and universities and to provide financial assistance for students in postsecondary education. During reauthorizations of the HEA, Congress makes changes to the legislation based on changing national and political priorities. But, it is important to remember that HEA was the response to deal with national problems of poverty and community development. It was President Lyndon Johnson’s own experience as a student and later as a teacher that was the underpinning of his work with Congress on HEA. As he wrote:

“I lived in a tiny room above Dr. Evans’ garage. I lived there three years before the business manager knew I occupied those quarters and submitted me a bill. I shaved and I showered in a gymnasium that was down the road. I worked at a dozen different jobs, from sweeping the floors to selling real silk socks. Sometimes I wondered what the next day would bring that could exceed the hardship of the day before. But with all of that, I was one of the lucky ones—and I knew it even then … I shall never forget the faces of the boys and the girls in that little Welhausen Mexican School, and I remember even yet the pain of realizing and knowing then that college was closed to practically every one of those children because they were too poor. And I think it was then that I made up my mind that this nation could never rest while the door to knowledge remained closed to any American.”

Debt & earnings premium

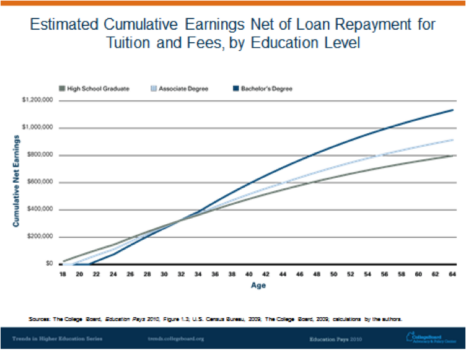

A combination of federal and private student loans in addition to federal and institutional aid has helped many students participate in education beyond high school. Yet, the question of students losing the “earnings premium” (average income gains due to postsecondary credential) despite loan indebtedness is a real concern, particularly as it relates to climbing federal default rates (9%) and undergrads with monthly payments greater than 25% of monthly income. But, for the typical student who borrows to cover tuition and fees at a community college and earns an associate degree two years after high school graduation, total earnings net of loan repayment exceed the total earnings of high school graduates by age 33, after 13 years of work. The typical four-year college graduate makes up for time out of the labor force and for paying tuition by age 30.

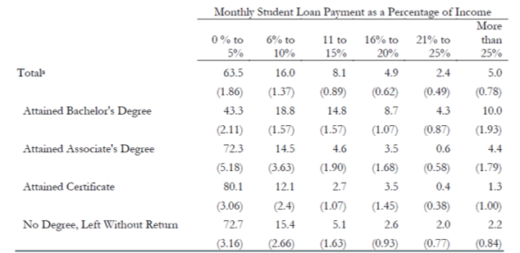

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the U.S Department of Education completed research over the summer which recommended that the two work with Congress to identify the necessary resources to provide a comprehensive picture of student borrowing that is inclusive of both federal and private student loans. In light of staggering headlines about graduates with six-figure debt loads, it is interesting to note that the majority (63%) of students who have federal and private student loans have monthly student loan payments that are 5% or less of their income, and 80% have monthly loan payments that are 10% or less of their income. On the other end of the spectrum, among individuals who did not attain a degree or certificate and had student loan payments, 88% had monthly payments of 10% or less of their income.

While most had manageable debt loads, this isn’t saying there isn’t a student loan debt problem–there is. Federal student loans were built to serve a different purpose. Loans provided access when prices were unaffordable for the most basic entry point of higher education. Today, for some, student loans serve as financing mechanisms to afford a higher-priced institution when a lower-priced institution would be possible without the additional debt burden. More debt always means more risk of not achieving the earnings premium. Still, we know that the debt problem is not reflected solely in student loan payments as a percentage of income. It is also reflected in parents being over-leveraged in additional ways not considered by the CFPB study. Those financing mechanisms include using home equity, federal PLUS loans, credit-card borrowing and tapping emergency and retirement savings to pay for college.

Relief for the middle class to contend with risings costs was reflected in the comments made by President George H.W. Bush during the HEA Reauthorization of 1992, “This act that I’m signing today gives a hand up to lower-income students who need help the most. But it also reaches out into the middle-income families, the ones who skipped a vacation and drove the old clunker so that their kids could go to college.” Still, in just the past 10 years, average tuition as a percentage of median earnings increasing from 27% percent to 38%. According to the How America Pays for College survey, parents decreased the average amount used from dedicated college savings funds to pay for college by 32%, although they increased the average amount withdrawn from retirement account savings by 59%. Among the families that used parent income to contribute to the cost of college in the 2011-12 academic year, the average value of the contribution was 20% higher than that reported the prior year.

Access to information

The recent strengthening of consumer protections under the CFBP and the Obama administration’s focus on college affordability tying federal campus aid to responsible campus tuition policies, has brought unprecedented access to information about campuses’ average indebtedness, graduation rates, net price and financial aid programs. The only problem is that students and their parents may not understand how to digest all this information and may not understand the personal implications for the statistics provided on sites like College Navigator and The College Affordability and Transparency Center. It also seems that the federal requirement for all schools to provide a net price calculator may not be achieving its desired outcome. According to Noel Levitz, 74% of students can’t find the Net Price Calculator never mind understand how to use it as part of a balanced college plan.

Resistance to correction

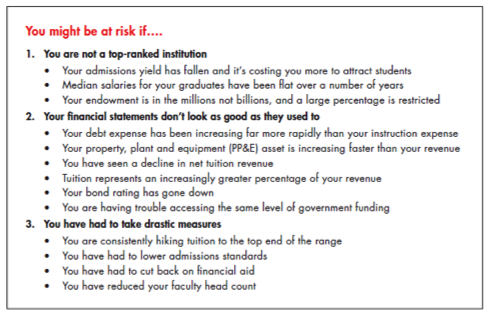

Institutions have more liabilities, higher debt service and increasing expense without the revenue or the cash reserves to back them up and are increasingly reliant upon tuition revenue. The lack of standard market forces means a resistance to correction. Bain & Co. presents a report in which it lauds the sector as a “cornerstone of our economic prosperity” and encourages it to meet the diverse needs of the U.S. student population, but condemns the “Robin Hood” pricing approach. The report also includes a tool to help readers understand which campuses are spending more than they can afford. The interactive graphic paints a bleak fiscal outlook, which includes several New England campuses.

Individual versus societal benefits

The often-cited “earn more than a million more dollars over a lifetime if you get a college degree” was effective in helping teens to correlate additional education to the personal financial benefits during the ‘80s and ’90s. However, today’s public policy (as reflected in state funding of higher education) and public discourse seems to focus only on the increase in personal income that, on average, results from higher education, rather than on the greater societal benefits–low unemployment, increased tax payments, health, civic engagement, low reliance on public assistance programs. A plethora of research documents the relationship between educational attainment and the economic strength of the New England states and our nation. Yet public policy has not reflected this reality. Declining state investment has been absorbed by the federal taxpayers and families. Again, President Johnson:

“I want to make it dear once and for all, here and now, so that all that can see can witness and all who can hear can hear, that the federal government—as long as I am president—intends to be a partner and not a boss in meeting our responsibilities to all the people. The federal government has neither the wish nor the power to dictate education. We can point the way. We can offer help. We can contribute to providing the necessary and needed tools. But the final decision, the last responsibility, the ultimate control, must, and will, always rest with the local communities.”

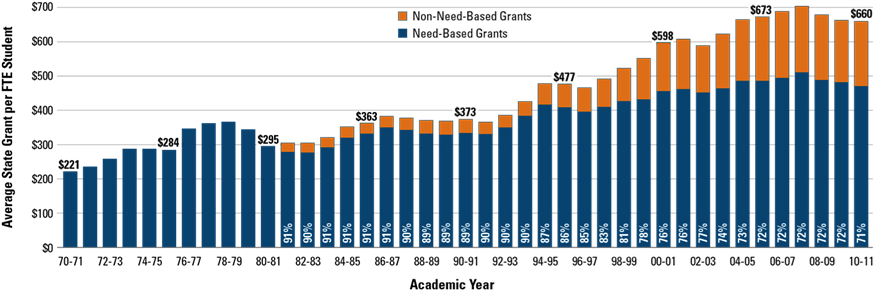

Among those states increasing aid, there is an upward trend in awarding grants based on academic merit without consideration of need. Yet, the intent of HEA was that funding higher education for low-income students would be a shared responsibility with states.

Click on the chart to enlarge.

The percentage of state grant dollars for undergraduate students distributed without regard to students’ financial circumstances increased from 9% in 1986 to 29% in 2011. The College Board’s Rethinking Student Aid study group of 2008 described that “the most important purpose for student aid is to expand participation of qualified low-income students in higher education.” Yet, states are increasing the percentage of non-need-based programs and the proportion of tuition and fees covered by the maximum Pell Grant has declined in the past 10 years. The Pell Grant covered 98% of average public four-year tuition and fees in 2002-03, but only 64% in 2012-13. And, of course, in New England, where the average public tuition and fees are among the nation’s highest, Pell covers an even smaller portion. Quietly, changes in the federal student aid program for 2012-13 reduced the income threshold for an automatic zero expected family contribution (EFC) from $30,000 to $23,000, thereby reducing eligibility for Pell for the some of our most vulnerable students. The Rethinking Student Aid study group recommends indexing the maximum Pell Grant to the Consumer Price Index (CPI). According to the group, “Since the poverty level is also indexed to the CPI, this practice will allow the Pell eligibility amounts to maintain their real, inflation-adjusted levels over time.”

From the gymnasium at Southwest Texas State College, his alma mater, President Johnson remarked on his valuation of a college education which recognizes the greater benefits:

“And in my judgment, this nation can never make a wiser or a more profitable investment anywhere … We will reap the rewards of their wiser citizenship and their greater productivity for decades to come … Here the seeds were planted from which grew my firm conviction that for the individual, education is the path to achievement and fulfillment; for the nation, it is a path to a society that is not only free but civilized; and for the world, it is the path to peace—for it is education that places reason over force.”

As we consider college costs, student aid and increasing access for New Englanders to achieve education beyond high school, we might just find that looking back to the intent of HEA provides insight about what we can do to improve the student aid system going forward.

Tara Payne is vice president of College Planning & Community Engagement at the NHHEAF Network Organizations.

[ssba]