The New England states, like the rest of the nation, are finally starting to show signs of a recovery from the Great Recession of 2008, albeit at different paces. Three of the states, however, still have unemployment rates that are about four percentage points above where they were before the recession began in 2007 (Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut). The smaller increases in unemployment rates in the remaining states (Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont) can be partially explained by an increasing fraction of people joining the ranks of the discouraged worker, or a changing demographic composition favoring older workers.

The New England states, like the rest of the nation, are finally starting to show signs of a recovery from the Great Recession of 2008, albeit at different paces. Three of the states, however, still have unemployment rates that are about four percentage points above where they were before the recession began in 2007 (Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut). The smaller increases in unemployment rates in the remaining states (Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont) can be partially explained by an increasing fraction of people joining the ranks of the discouraged worker, or a changing demographic composition favoring older workers.

Arising from this recovery, America will find itself on a collision course with the future: not enough Americans are completing college. In its most recent report, Help Wanted: Projections of Jobs and Education Requirements Through 2018, the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce has shown that by 2018, we will need 22 million new college degrees to meet employers’ demand—but at current graduation rates, we will fall short of that number by at least 3 million postsecondary degrees, associate or better.

This 3 million shortfall is the equivalent of 300,000 additional graduates each year between now and 2018, or a 10% a n nual increase in degrees conferred by colleges and universities nationwide. College degrees are not the only kind of credential the American economy will come up short on; we will also need at least 4.7 million new workers with postsecondary certificates. At a time when every job is precious, this shortfall will mean lost economic and social opportunity for millions of American workers.

We cannot afford to linger on memories of an economy that promised well-paying jobs for anyone who graduated from high school. Over the past three decades, higher education has become a virtual must for American workers. Between 1973 and 2008, the share of jobs in the U.S. economy that required postsecondary education increased from 28% to 59%. According to our projections, the future promises more of the same. The share of postsecondary jobs will increase from 59% to 63% nationally over the next decade. High school graduates and dropouts will find themselves largely left behind in the coming decade as employer demand for workers with postsecondary degrees continues to surge.

In addition to the increasing education requirements of occupations, postsecondary education has become the threshold requirement for a middle-class family income. In 1970, almost 60% of high school graduates were in the middle class. By 2007, the share had fallen to 45%. Over that same period, people with college degrees (bachelor’s and graduate degrees) have either stayed in the middle class or boarded the escalator upward to the highest three family income deciles.

The increased earning power conferred by postsecondary education and training is both tangible and lucrative over a worker’s lifetime. The range in lifetime earnings by educational attainment is greatest between high school dropouts and professional degrees—a range of $1,198,000 to $4,650,000, or a difference of $3,452,000.

Postsecondary education is your umbrella to weather the storm of economic adversity. During this recession, high school dropouts were three times as likely to be unemployed as holders of bachelor’s degrees or better. Yet, a higher level of education alone is not the answer to greater opportunity. Occupational choice and to a lesser extent, industrial choice also determines wages and economic prospect. For instance, 43% of workers with licenses and certificates in fields such as drafting or electronics earn more than their colleagues with an associate degree. About 27% of workers with licenses and certificates earn more than employees with a bachelor’s degree, and 31% of those with associate degrees earn more than their counterparts with a bachelor’s degree according to the National Education Longitudinal Study, 2000.

These are the tangible benefits to postsecondary education. There are unmeasurable benefits as well. For example, education an educated citizenry can continue to defend and promote democratic ideals. Ultimately, however, the economic role of postsecondary education is central, especially in preparing American youth for work and helping adults stay abreast of economic change.

Our Help Wanted report demonstrates that employers will increasingly demand proof of competency of workers, not only in terms of formal degrees, but also through industry-based certification programs and credentials that require periodic renewals. We must create the appropriate infrastructure to generate:

- Highly structured “learn and earn programs” like apprenticeships and on-the-job training;

- Compressed training programs that integrate basic skills preparation with fast and intensive occupational training leading to postsecondary certificates with demonstrated labor market value;

- Effective job and skill counseling for unemployed and underemployed experienced workers and working students to provide accurate information on earnings potential and career pathways;

- Systems for maximizing the labor market value of postsecondary education and training programs by tying postsecondary transcript data with employer wage records data currently housed in the U.S. Employment Services; and

- Statewide and nationwide development of online job search systems that match job openings and career pathways to available courses offered by nearby postsecondary institutions and as online courseware.

The New England states should make a firm commitment to improve access, reduce cost, improve efficiencies and better align students with viable job opportunities. Such a commitment is even more relevant as the U.S. Government considers requiring short-term credentialing programs to pass an earnings potential litmus test in order to be eligible for federal student aid programs.

New England: A Look at the Numbers

Table 1: Percentage of jobs that will require postsecondary education by 2018

| New England states | Percentage of jobs that will require a postsecondary education (2018) | Postsecondary education intensity ranking (2018) |

| Maine | 59% | 32nd |

| New Hampshire | 64% | 15th |

| Vermont | 62% | 23rd |

| Massachusetts | 68% | 4th |

| Rhode Island | 61% | 28th |

| Connecticut | 65% | 11th |

|

|

The educational demand for jobs in New England in the next decade is as diverse as the states themselves. Relative to the national average of 63% of jobs requiring postsecondary education and training, three states, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Hampshire (68%, 65% and 64% respectively) are above average; Rhode Island and Vermont are just below the national trend. Due to a variety of economic factors explained in greater detail below, Maine demonstrates below average proportions of jobs (59%) requiring postsecondary education and training in the future. It is 32nd in the nation.

These outcomes are influenced by many factors including the industrial make-up of the state, educational characteristics of the workforce and, increasingly, by the occupations that make up the different industries. Career ladders are increasingly tied to occupations, that is, what you do, rather than where you do it. People no longer work their way up from the loading dock to the CEO’s office; instead they get educated and trained to perform a specific role, and progress upwards in an occupational hierarchy. Some occupations are tied to particular industries, such as healthcare occupations, but in many other cases, people cross between industries throughout their career. Someone trained in a sales occupation can make a living selling travel deals, computer equipment, and then stocks and bonds. Though these are all different industries, the jobs the individual holds will continue to require higher and higher levels of formal education tied to his or her occupation.

Occupations, Industries and Education

Of all the occupations, Healthcare Professional and Technical, Education, STEM, Community Services and Arts and Managerial and Professional Office have the highest concentrations of jobs requiring some college education, a postsecondary vocational certificate or degree.

Among industries, our forecasts show that Information Services, Private Education Services, Government and Public Education Services, Financial Services and Professional and Business Services industries, have the highest concentrations of jobs requiring some college education, a postsecondary vocational certificate or degree. Furthermore the education-intensive industries of Information Services, Wholesale and Retail Trade Services, and Healthcare Services are the three fastest-growing industry sectors, while the traditional, less education-intensive base industries of Manufacturing and Natural Resources rank seventh and 13th. This means that states that use that particular occupational and industrial mix most intensely, by definition, will require the highest concentrations of postsecondary training of its workforce.

Overall, both occupations and industries with the fastest-growing output have the highest education requirements. Thus, economic growth in the coming decade will be driven by the ongoing shift to a “college economy.”

Maine Will Fail to Attract High-Paying Jobs in Growing Sectors

In 2018, 59% of all jobs in will require postsecondary education and training beyond high school. The current job mix for Maine shows below average concentrations of workers in Private Education, Professional and Business Services, Information and Private Education Industries and above average concentrations in Manufacturing and Natural Resources. These characteristics contribute to a subdued demand for postsecondary education in Maine, compared with other New England states. There is an extraordinarily high demand for workers with high school diplomas, ranking Maine third in the nation in the proportion of its jobs for high school graduates.

Table 2: Snapshot of Educational demand for Total Jobs (2008 and 2018)

|

|

2008 | 2018 |

| High school dropouts | 36,900 | 37,000 |

| High school graduates | 240,200 | 242,300 |

| Some college | 72,000 | 74,800 |

| Associate | 132,600 | 135,800 |

| Bachelor’s | 122,700 | 128,000 |

| Graduate | 53,900 | 57,700 |

In 2018, there will be more jobs in Maine whose highest level of education is high school than jobs for holders of bachelor’s degrees and graduate degrees combined. The high school dropouts will still be concentrated in traditional industries like natural resources and manufacturing and occupations such as installation, maintenance and repair jobs, production occupations and farming fishing and forestry. Jobs requiring postsecondary education will span the entire occupational spectrum, but are generally organized in Education, Sales and Office and Administrative Support, Healthcare Practitioners and Managerial fields.

Maine will create 196,000 job vacancies from new jobs and from job openings due to retirement, 115,000 of which will be for those with postsecondary credentials.

Today, Maine is on par with the rest of the nation in the proportion of its residents with a college degree. But the state will fall behind in this measure if current trends in college completions and net migrations continue, according to research by the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (NCHEMS).

New Hampshire Poised for a Boom in Post-recession Postsecondary Jobs But Will its Workers Be Prepared?

By 2018, 64% of jobs in New Hampshire will require postsecondary education and training beyond high school. The current job mix for New Hampshire shows above average concentrations of workers in Professional and Business Services, and Healthcare Industries. These characteristics contribute to an elevated demand for postsecondary education in New Hampshire, compared to her New England sister states. There is particularly high demand for workers with bachelor’s degrees, ranking New Hampshire seventh in the nation in the proportion of its jobs for high school graduates. New Hampshire will show the biggest growth of all the New England states in net new jobs, 11%, by 2018. The largest growth in net new jobs created will require bachelor’s degrees (11%) or graduate degrees (13%).

Table 3: Snapshot of Educational demand for Total Jobs (2008 and 2018)

|

|

2008 | 2018 |

| High school dropouts | 47,000 | 50,700 |

| High school graduates | 215,000 | 232,600 |

| Some college | 74,200 | 83,300 |

| Associate | 137,200 | 151,000 |

| Bachelor’s | 152,200 | 171,800 |

| Graduate | 68,900 | 79,900 |

Job opportunities for those with postsecondary education and training will be twice as large as those for high school graduates in 2018. Bachelor’s degree jobs will increase by close to 20,000 over the 10-year timeframe. The jobs for holders of bachelor’s degrees will be concentrated in white-collar fields such as Computer and Mathematical Sciences, Education and Managerial jobs. Substantial numbers of jobs also exist for holders of associate degrees in Sales and Office and Administrative Support fields.

New Hampshire will create 223,000 job vacancies, including new jobs and replacement jobs due to retirement, 141,000 of which will be for those with postsecondary credentials.

Vermont to Create Thousand of Postsecondary Jobs Despite Slow Growth

By 2018, 62% of Vermont jobs will require postsecondary education and training beyond high school. The current job mix for Vermont shows above average concentrations of workers in Private Education and Healthcare Services. These characteristics contribute to a great demand for postsecondary education in Vermont, compared with other New England states. There is a relatively high demand for workers with bachelor’s degrees, ranking Vermont ninth in the nation in the proportion of its jobs for holders of bachelor’s degrees. Graduate degree jobs will grow by 8%, higher than any other education category over the 10-year timeframe. Despite these achievements, however, net new jobs will only grow by 3%– the second lowest rate of all New England States.

Table 4: Snapshot of Educational Demand for Total Jobs (2008 and 2018)

|

|

2008 | 2018 |

| High school dropouts | 18,300 | 18,500 |

| High school graduates | 112,600 | 113,400 |

| Some college | 34,500 | 35,800 |

| Associate | 59,500 | 61,000 |

| Bachelor’s | 73,800 | 77,000 |

| Graduate | 34,600 | 37,500 |

The distribution of jobs for those with postsecondary education and training will be very diverse in 2018. Jobs at the top end for holders of bachelor’s degrees or better will outstrip jobs in the middle for holders of “Some College” or associate degrees by 18,000. Education and Healthcare will be the most substantial employers of college-educated citizens of Vermont. Sales jobs, Food preparation and Serving and Office and Administrative support will dominate the demand for holders of high school diplomas.

Vermont will create 100,000 job vacancies from new jobs and job openings due to retirement, 62,000 of which will be for those with postsecondary credentials.

Today, Vermont ranks substantially above the rest of the nation in the proportion of its residents with a college degree and will remain ahead in this measure if current trends continue, according to NCHEMS research.

Massachusetts to Produce Half of All Postsecondary Job Vacancies in New England

By 2018, 68% of all jobs in Massachusetts will require postsecondary education and training beyond high school. The current job mix for Massachusetts shows above average concentrations of Healthcare Services and Professional and Business Services. These characteristics result in an elevated demand for postsecondary education in Massachusetts compared with her New England sister states. Not only is the demand for postsecondary education in training highest in Massachusetts of the New England states, that demand is concentrated in bachelor’s degrees or better. Massachusetts ranks first in the nation in the proportion of its jobs for bachelor’s degrees and second in the proportion of its jobs for graduate degree holders. Bachelor’s degree and graduate degree jobs will have the largest growth in net new jobs created at 7% and 9% respectively.

Table 5: Snapshot of Educational Demand for Total Jobs (2008 and 2018)

|

|

2008 | 2018 |

| High school dropouts | 271,000 | 275,700 |

| High school graduates | 934,400 | 954,000 |

| Some college | 314,300 | 331,000 |

| Associate | 585,200 | 608,700 |

| Bachelor’s | 855,800 | 915,500 |

| Graduate | 535,000 | 583,500 |

There will be over 2.5 times as many jobs for holders of some postsecondary education and training than jobs for high school graduates by 2018. Graduate jobs will be concentrated in Education and Healthcare Professional jobs while bachelor’s degree jobs will be concentrated in Office and Administrative Support and Managerial professions.

Massachusetts will create 1 million job vacancies from growth and retirement, 707,000 of which will be for those with postsecondary credentials.

Today, Massachusetts is the best performing state in the nation in the proportion of its residents with a college degree and will remain on top if current trends in college completions and net migrations continue, according to NCHEMS research.

Percentage of Jobs for High School Dropouts Highest in Rhode Island

By 2018, 61% of all Rhode Island jobs will require postsecondary education and training beyond high school. The current job mix for Rhode Island shows relatively high concentrations of workers in Healthcare and Leisure and Hospitality, and below average concentrations in Professional and Business Services and Finance. These characteristics result in a slightly lower demand for postsecondary education in Rhode Island, compared to the rest of New England. There is a very high demand for workers with graduate degrees, leading to Rhode Island ranking ninth in the nation in the proportion of its jobs for holders of graduate degrees.

Table 6: Snapshot of Educational demand for Total Jobs (2008 and 2018)

|

|

2008 | 2018 |

| High school dropouts | 56,600 | 58,000 |

| High school graduates | 144,400 | 149,600 |

| Some college | 48,200 | 51,000 |

| Associate | 96,500 | 101,000 |

| Bachelor’s | 103,000 | 109,600 |

| Graduate | 54,700 | 59,500 |

Eleven percent of jobs in 2018 will require a high school diploma—the highest proportion of high school jobs in the New England states. Job opportunities for those with middle education levels—associate degrees and “Some College” will be just as large as job opportunities for high school graduates. These “middle-skill” jobs will be concentrated in Office and Administrative Support, Sales and Blue-collar jobs by 2018. Bachelor’s degree holders will be concentrated in Education and Managerial occupations.

Rhode Island will create 153,000 job vacancies due to both retirement and job growth, 93,000 of which will be for those with postsecondary credentials.

Today, Rhode Island ranks ahead of the nation in the proportion of its residents with a college degree, and NCHEMS research suggests the state will perform substantially above average in this measure if current trends continue.

Connecticut to Produce a Quarter of All Postsecondary Job Vacancies in New England

By 2018, 65% of all Connecticut jobs will require postsecondary education and training beyond high school. Connecticut’s economy features above average concentrations of workers in Healthcare, Professional and Business Services, and Financial Services. These characteristics result in an elevated demand for postsecondary education in Connecticut, compared to the rest of the region. There is an extraordinarily high demand for workers with bachelor’s degrees or better, ranking Connecticut 8th in the nation in the proportion of its jobs for bachelor’s degrees holders and fourth nationally in the proportion of jobs for those with graduate degrees.

Table 7: Snapshot of Educational demand for Total Jobs (2008 and 2018)

|

|

2008 | 2018 |

| High school dropouts | 138,500 | 144,800 |

| High school graduates | 536,600 | 561,900 |

| Some college | 155,900 | 166,400 |

| Associate | 345,000 | 364,400 |

| Bachelor’s | 395,100 | 426,100 |

| Graduate | 257,800 | 281,800 |

Jobs for holders of a bachelor’s degree of better will exceed the number of opportunities for workers with middle skills (Some College or Associate’s degrees) or holders of a high school diploma only. Graduate degrees and bachelor’s degrees will be concentrated in Education and Healthcare fields.

Connecticut will create 564,000 job vacancies from new jobs and job openings due to retirement, 359,000 of which will be for those with postsecondary credentials.

Today, Connecticut is above the rest of the nation in the proportion of its residents with a college degree. NCHEMS research however, has estimated that this state will fall behind if current trends in college completions and net migrations continue.

Bridging the Gap: Developing a Career Development Information System

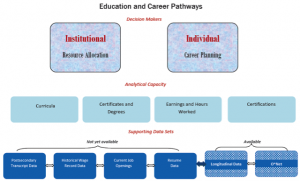

The Help Wanted report highlights the need in the U.S. economy for more workers with postsecondary education and training in order to leverage economic opportunity. The next stage of this analysis should discuss the data we need to better align curricula to training and to jobs. In the above diagram, the units of analysis at the pinnacle are the decision-makers—both from an institutional perspective of placing scarce resources to their most efficient use—and from an individual’s perspective of making long-term career decisions and selecting the education and training required to achieve their goals.

The U.S. is unable to help people match their educational preparation with their career ambitions—but not because it cannot be done. All the information required to align postsecondary educational choices with careers is available, but unused. The forecast in this report demonstrates that projecting education and job requirements is technically feasible with a minimum amount of error. We need to build analytical capacity to empirically answer the questions that parents, young adults and educators alike have been asking all along. The mechanism required should connect the college supply engine (transcript data) to workforce development (unemployment wage records) to opportunities in real time (current job openings).

The data apparatus in the figure above closes the loop of institutional decision-making and individual career choices and outlines a system that could fully address the following challenges:

- Are some credentials worth more than others, and if so by how much? Connecting wage records to transcript data will allow us to give a more nuanced answer than the standard hierarchical relationship between formal education levels and compensation differentials.

- What are the successful education and career pathways? To what extent have the steppingstones of certificates achieved their goals of providing upward mobility for lower-income Americans? An analysis of longitudinal survey data that traces individual attainment, occupational choice and wage outcomes is the only way to test the long run successes of individuals as they navigate their lives.

- Are students able to define the distance in bite-sized attainable clusters of courses between their current level of attainment and the attainment required to gain access to their desired profession? A “learning exchange” could connect the students to current job openings and a sample of colleges and universities that offer the courses he or she needs to attain that job.

- How closely aligned are curricula to the knowledge, skills, abilities, work activities and interests of occupations? How effective are institutions of higher learning at preparing their students for the tasks and work activities that they will encounter in the workplace? For example, the O*NET database created by the National O*Net Consortium and funded by the U.S. Department of Labor specifies the full set of occupational competencies required for success in particular occupations and related clusters of similar careers. Currently, its primary use is as a counseling tool for career planning, delivered online through a user-friendly interface. Its potential remains largely untapped.

- The human capital landscape has evolved beyond traditional formal diplomas and degrees to include industry-based certifications and state required licenses. How valuable are industrial-based certifications, how prevalent are they in the society and to what is their marginal value to formal education levels?

The current economic climate further heightens the need to create data system that increase the efficient allocation of scare resources, reduces employment search time due to mismatch and asymmetric information and provides decision makers with the resources they need to better align career decisions with long term economic interests. To do otherwise risks leaving hundreds of thousands of workers behind, as the economy recovers and builds for the future.

And that would be a dismal recovery, indeed.

Anthony P. Carnevale is director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Nicole Smith is senior economist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

[ssba]