Over the past decade, policymakers and business leaders across New England have been concerned that the region’s slower population growth and loss of residents to other parts of the country will lead to a shortage of skilled labor—particularly when the baby boom generation retires. Prior to the Great Recession, the concern was that an inadequate supply of skilled workers would hamper future economic growth by creating barriers for companies looking to locate or expand in New England. More recently, the worry is that the lack of skilled workers will make it difficult to fill jobs that are in high demand as the economy recovers—many of which are likely to require postsecondary education and training—thereby slowing the region’s recovery. That means having not only a sufficient number of skilled workers but also a workforce with the right mix of skills to fill the jobs that are likely to be generated by the region’s economy.

Given current labor market conditions, it seems hard to imagine that New England could possibly lack a sufficient number of skilled workers in the not-so-distant future. Census projections for 2020 show that the number of individuals ages 15 to 24 years in New England who are slated to enter the labor force in the coming decade will be 15% smaller than the number of individuals ages 55 to 64 years who are likely to leave the labor force as they retire. Moreover, while it is true that this gap is likely to occur in several other U.S. regions, the U.S. Census Bureau projects that New England will have the largest potential shortfall, while some regions will continue to experience a surplus of workers.

Indeed, a potential mismatch between the level of skill among the population and the demand by employers over the next two decades may already be underway. The structure of the U.S. economy has changed dramatically over the past few decades, leading to an increase in the demand for more highly educated workers. The reduced role of the manufacturing sector, the increased importance of the professional service and knowledge sectors, advancements in technology, and the spread of globalization are evidence that the ways in which we “do work” have fundamentally changed. As a result, employers are demanding that workers obtain more formal education and training—often requiring some type of postsecondary degree or certificate—in addition to greater technical proficiency and interpersonal skills than in the past.

However, it is unclear how large this potential labor mismatch might be and whether this issue is unique to New England or is pervasive across the nation. Our simulations indicate that there is likely to be a potential mismatch between the level of education and skill among the population and that which will be demanded by employers in the coming decades—particularly among middle-skill jobs that require some postsecondary education but less than a bachelor’s degree. And although any potential mismatch is likely to be alleviated to some degree by a variety of market responses, the magnitude and nature of the problem suggests that there is still a role for public policy. In particular, rethinking how best to invest in our education and training programs that serve middle-skill workers—such as those based at our community colleges—seems warranted.

Supply of middle-skill workers has not kept pace

The reason policymakers and business leaders are so concerned about there being a sufficient number of skilled workers in New England is that the region’s population of working-age adults with postsecondary education and training has been growing more slowly than that in the rest of the United States. Since 1990, the number of individuals ages 25 to 64 years in the region with any postsecondary education has risen by only 29% compared with 43% nationwide, and has been growing more slowly with each passing decade. Moreover, while the rate of growth has slowed across the country, the slowdown has been sharper for New England than most other regions primarily due to slower population growth and, to a lesser extent, greater net domestic outmigration.

Interestingly, the slowdown in the number of college-educated workers differs by the level of skill. Among “middle-skill” individuals (those with some college or an associate degree), New England’s growth rate has consistently been below that of the nation and since 2000, the region has even experienced a small decrease in this population (see Figure 1). The slowdown has been particularly acute in southern New England, with this population shrinking in both Connecticut and Massachusetts since 2000. In contrast, New England’s population of “high-skill” individuals (those with a bachelor’s degree or higher) grew at a rate that exceeded the nation during the 1980s, slowing only in recent decades.

Not surprisingly, the distribution of educational attainment in New England—or the region’s mix of skills—has shifted more rapidly toward the upper end while lagging in the middle. Between 1980 and 2006, although the share of “middle-skill” individuals in the region increased from 19% to 26%, it still fell short of the share nationwide. In contrast, the share of “high-skill” individuals in the region—those with a bachelor’s degree or higher—nearly doubled over the same period.

New England has experienced slower growth in the supply of skilled workers compared than the nation has. But is it the case that supply has fallen short of demand? Looking at trends in relative wages over time suggests that the demand for skilled workers has outpaced supply in both the region and the nation. Over the past several decades, the labor market has experienced rising demand for college-educated workers as evidenced by the rapid increase in their earnings relative to those of less-educated workers. As a result, employers are willing to pay a premium for workers with any postsecondary education despite there being more of them. Moreover, this premium has been growing over time, indicating that the demand for such workers has continued to outpace their supply.

While this situation is not unique to the region, New England differs from the nation in one important regard: The imbalance between the supply and demand for labor is greatest among middle-skill workers—those with only some college or an associate degree. While the premium for middle-skill workers with some college or an associate degree has accelerated relative to the nation, the premium for bachelor’s degree recipients in the region has leveled off. For example, in 1980, men with an associate degree earned 13% more per hour than men with only a high school diploma. By the year 2006, this premium had more than doubled to 30%. For individuals with only some college, the premium has grown even more rapidly, from 6% to 19%. These growing wage premiums suggest that as the share of middle-skill workers has expanded less rapidly in New England compared to elsewhere in the country, the imbalance between supply and demand has become more severe.

Is this mismatch isolated to a few key areas or is spread more broadly throughout the economy? Although industries that employ a greater share of college-educated labor have been growing more rapidly in New England, most of the increased demand for workers with postsecondary education is due to greater use of college-educated workers within all industries. Indeed, since 1990, the share of workers who hold a college degree has increased in nearly all of the major industrial sectors in New England—even those that have not typically employed a high fraction of skilled workers. For those with an associate degree, over 90% of total employment growth comes from greater use of such workers within all industries, indicating that this trend is not just isolated to a few key sectors of the economy but is fairly widespread. At the same time, the wage premium for college-educated workers increased within most industries—despite there being more workers who were college graduates—even within industries with relatively low shares of college-educated workers—indicating rising demand throughout the economy.

Moreover, these demand trends are not likely to reverse themselves. Indeed, a large literature has documented increasing skill-wage premiums at the national level, noting several potential causes that are not easily reversed. These include increasing technological change that favors more educated workers, growth in international trade that has displaced work done by less-educated workers, and declining labor market institutions (e.g., unions and minimum wage laws) that have traditionally protected employment and wages of workers without a college education. In addition, recent job vacancy rates indicate that the region has experienced high vacancy rates relative to the nation that have persisted throughout the recession, particularly in key sectors of the economy such as management, business and financial operations, computer and mathematical sciences, and healthcare.

Supply of middle-skill workers will be constrained

While New England boasts one of the most educated populations in the U.S., significant demographic changes suggest that the supply of skilled workers may not keep pace with demand in the future. The retirement of the baby boomers—a well-educated group—will result in large numbers of college-educated workers leaving the labor force—particularly in New England, which has a relatively high share of workers ages 55 to 64 years. In addition, the population of native recent college graduates who are needed to replace those retiring has been growing more slowly in New England than in other parts of the nation. Finally, although immigrants are an increasing source of population and workforce growth in the region, these individuals often lack the formal education and English language skills that employers require. As a result, there is likely to be a potential mismatch between the level of education and skill among the population and that which will be demanded by employers in the coming decades.

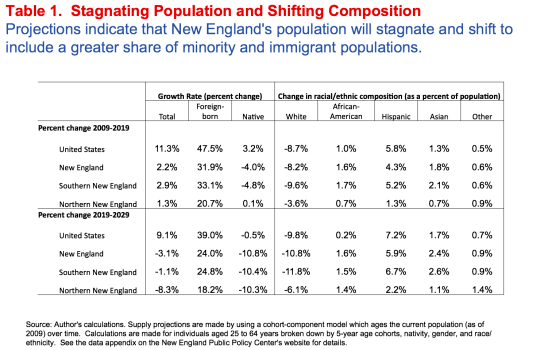

Looking forward, our projections indicate that the working-age population in New England will stagnate and even shrink over the next two decades while that of the nation will grow. Using a cohort component model, the region’s population of individuals ages 25 to 64 years is projected to grow by only 2.2% between 2009 and 2019 and then shrink by 3.1% between 2019 and 2029 (see Table 1). [i] The population decline is particularly evident in northern New England due to slower growth among the foreign-born, according to research by the New England Public Policy Center. In contrast, the nation’s working-age population is projected to grow by nearly 10% in each of the coming decades.

In addition, the composition of the region’s labor force will shift to include a greater share of minority and immigrant populations, particularly in the southern part of the region. For example, the share of New England’s labor force that is non-Hispanic white falls by more than 8% in each decade (see Table 2). Among the region’s minority populations, the greatest increase is in the share of Hispanic workers, which more than doubles. These shifts are even greater for southern New England where the foreign-born population is projected to grow more rapidly.

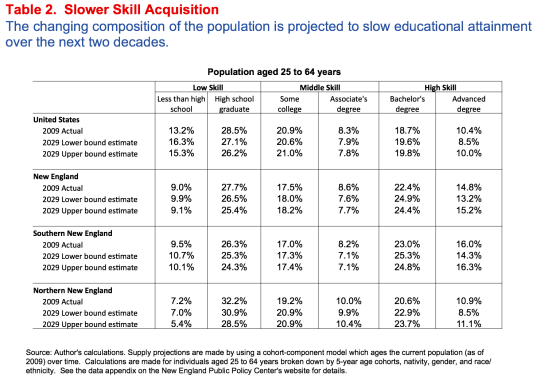

The changing composition of the population will put downward pressure on New England’s education distribution since foreign-born and minority groups typically have lower levels of attainment than the native white population. However, recent trends also show that individuals, particularly minorities, often continue to obtain additional education and training over time as they age. These two forces are captured by our “lower- and upper-bound” measures of future labor supply. The lower-bound measure reflects only changes in the composition of the labor force, while the upper-bound measure also allows for increasing educational attainment over the lifecycle.

Our projections indicate that the changing composition of the population will lead to slower skill acquisition in both New England and the nation. Among middle-skill workers, the share of individuals completing an associate degree is projected to fall by roughly a percentage point, even though the share of individuals with some college is projected to increase slightly (see Table 2). That is because completion rates at the associate degree level are extremely low and have shown little improvement over the past decade. So even if more high school graduates choose to attend community college, degree completion rises by much less. The southern part of the region is driving much of this trend; in contrast, northern New England continues to maintain or even slightly increase its share of middle-skill workers.

Will there be a mismatch?

How will the education/skill levels of future labor force participants stack up against those demanded by firms over the next decade? To examine this, we make employment projections by detailed occupation and “assign” jobs to different levels of education. We then sum employment over all occupations by each education category to get the total number of workers “demanded” by each education level.

Again, we make two sets of projections. The lower-bound projection assigns jobs to different levels of education using the distribution of educational attainment for workers currently in each detailed occupation. This allows us to capture the variation across education categories within occupations rather than assigning all jobs in an occupation to a single education level. This is what we think of as “maintaining the status quo”—the distribution of workers that employers would demand if they were to fill both old vacancies and new job openings with workers who have the same level of education as those who hold those types of jobs now. As such, it reflects only shifts in demand due to job growth across occupations.

However, we have seen that much of the increase in labor demand for college-educated workers stems from an increase in demand within occupations. The upper-bound projection applies the change in the education distribution for each detailed occupation between 2000 and 2006 to the current distribution to project what demand by each education category would look like if the prevailing trends continued. That is what we think of as “upskilling”—the projected distribution of workers that employers would demand if they were to fill both old vacancies and new job openings with workers who have increased their level of education to a similar degree as workers who have held those jobs in the past. As such, it reflects shifts in demand both across and within occupations.

Some researchers have suggested that instead of using the educational distribution of individuals currently employed in a given occupation, one should rely on education and training requirements developed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) such as O*NET. While O*NET can be used to learn more about the tasks and work activities for a given occupation, it still relies on a survey of respondents to determine the education level required—similar to the methodology we use here. The difference is that the BLS then categorizes the occupation into one of five job zones, thereby eliminating the variation in educational attainment within each occupation. Yet employer needs are likely to differ across specific positions, firms and industries and for entry-level versus more advanced positions. In addition, the training requirements approach does not incorporate the potential need for upgrading of skills in the future.

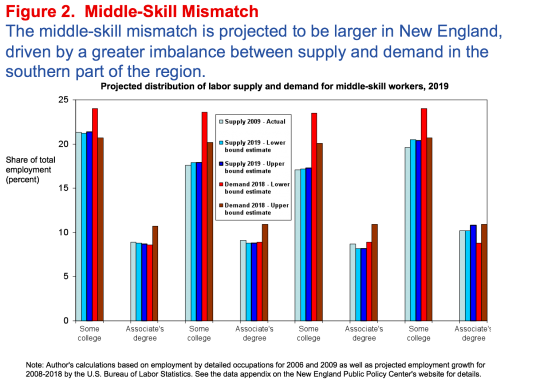

Our projections show that labor demand in New England over the coming decade will continue to shift toward high-skill workers while remaining relatively constant for workers in the middle of the education distribution. According to our projections, by 2018, the number of workers demanded in New England is likely to exceed supply and this imbalance will not be distributed evenly across skill categories. For example, the number of middle-skill workers is projected to fall short of demand by roughly 15% nationwide versus a 30% shortfall in New England.

How well does the overall mix of skills likely to be demanded by employers match up with the shares of the population by education level? Looking at the relative distribution of jobs versus workers indicates that any potential mismatch is likely to be largest among those in the middle-skill category. In this category, labor supply is likely to fall short of demand by 4 to 6% in New England versus 1% to 2% for the nation (see Figure 2). The mismatch is greatest in southern New England where the supply of middle-skill workers has been shrinking over time.

However, it is crucial to note that the future path of employment will be determined not only by the demands of employers and the skills of existing workers but also by future adaptations that we cannot anticipate. Indeed, there are likely to be some labor market adjustments over the next decade in response to these gaps on the part of both employers and workers. In the past, as the demand for skilled workers outpaced supply, the wages of those with any postsecondary education increased relative to those with less education. In the future, we can expect to see some of the same adjustments. And as wages rise, both workers and firms are likely to respond. For example, younger workers are likely to respond by migrating into the area from other parts of the country. Alternatively, older workers may choose to stay in the labor force longer, delaying retirement. Finally, in the long run, entering cohorts of workers are likely to obtain more education and training in response to higher wages.

Yet even when we make adjustments to account for market forces, labor supply in New England continually falls short of labor demand. Extrapolating from recent trends in high school graduation rates, college continuation rates, and college completion rates, our simulations show that additional educational attainment in response to rising wage premiums is not likely to be large enough to fill the projected skills gap over the next two decades—particularly among middle-skill workers. In fact, the size of the market response would have to be unprecedented to fill the gap. For example, net migration of middle-skill workers would have to increase by roughly 70,000 individuals per year over the next decade—yet New England typically experiences net out-migration in most years.

In addition, data limitations will cause our analysis to mask potential shortfalls within certain occupations. This is particularly true of many middle-skill jobs that require specific technical training that cannot be met by more general postsecondary education. For example, having an abundance of individuals with some college or an associate degree will do little to alleviate the persistent shortage in registered nurses unless those individuals obtain a nursing degree.

All in all, the trends described here are not likely to be a temporary phenomenon. The demand projections reflect an ongoing trend that was well underway before the Great Recession where technological change and other forces have been increasing the demand for more educated workers for decades. Similarly, the supply projections stem from demographic trends that have been on the horizon for quite some time and are likely to continue into the next decade and beyond

Will market forces fill the gap?

Although market forces are likely to lessen the severity of any future imbalance between the supply and demand for skilled labor to some extent, market imperfections and other constraints suggest that there is still a role for public policy. Our estimates showed that relying on individuals to obtain additional education and training in response to wage differentials is not likely to meet future demand—a scenario that we have seen over time as wage premiums for those with any postsecondary education and training have been rising for decades. Workers in the middle of the skills distribution are less mobile and have fewer resources than those at the top. Private-sector investments in such training are also limited as firms are often reluctant to invest in workers if it is fairly easy for other firms to hire workers away.

Providing individuals with the education and training they need to qualify for occupations that are likely to be in high demand in the future seems warranted. Indeed, despite greater automation and offshoring, middle-skill jobs still account for roughly one-third of New England’s employment—suggesting there will be a continued need for workers with some postsecondary education and training that is less than a bachelor’s degree. What’s more, at least half of all middle-skill jobs are in occupations such as healthcare (nurses, EMTs, therapists), sales (retail sales and supervisors), protective services (firefighters, police officers, correctional workers), education (teacher assistants), and office and administrative support (executive/medical/legal secretaries and administrative assistants). These are all growing occupations that typically rely on some interpersonal interaction that cannot be outsourced or automated, suggesting that perhaps firms have reached the limits of feasibility in terms of applying such strategies given their production processes.

Our results suggest that, in addition to ongoing efforts to expand more traditional four-year baccalaureate attainment, policymakers should consider specific education and training policies that target growing categories of middle-skill jobs. This is particularly true for southern New England where the mismatch is driven not only by having fewer workers but fewer workers with the right mix of skills. According to our projections, if the college continuation rate of both entering and existing cohorts (up to age 39) were raised by 20%, the gap would be reduced by one-third to one-half over the course of the decade. Such a large and immediate gain may not attainable; this rough calculation is simply meant to demonstrate the magnitude of change that would be required.

Rethinking how best to invest in our education and training programs that serve middle-skill workers, such as those based at community colleges, could benefit both the region and its residents. Yet the higher education system in New England seems skewed toward private institutions that produce bachelor degree holders—particularly in the southern part of the region. Typically the southern New England states have invested less in their public institutions in terms of appropriations per-capita than the national average. In addition, the completion rates of community colleges in southern New England lag behind the nation.

Yet increasing postsecondary education and training for middle-skill workers would require overcoming a number of challenges. We have shown that future gaps stem from changes in the composition of the labor force toward greater shares of immigrant and minority populations. Further gains in educational attainment among these traditionally disadvantaged groups would require significant investments in financial aid. In addition to financial assistance, community college students often face greater challenges to completion than those attending four-year institutions. Finally, postsecondary training at community colleges should be career oriented and focus on preparing students for middle-skill jobs that are expected to be in high demand.

These challenges should not stand in the way of progress. Strengthening community colleges can be a win-win-win for students, employers and the region. For students, it can be specialized training for a middle-skill career or an inexpensive steppingstone to a four-year degree. For employers, it can be a local partner to develop job-specific training programs for current employees or a nearby source for future recruiting. For the region, it can be a workforce development tool that is used to strengthen growing sectors of the economy while serving to reduce economic inequality and poverty.

——————————————————————————————————————————-

Alicia Sasser Modestino is a senior economist at the New England Public Policy Center at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Email: Alicia.sasser@bos.frb.org. The full report, including more detailed information for the New England states, is available at http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/neppc/.

[i]

To project the future population over the next two decades, we begin with a baseline population of individuals ages 25 to 64 years for 2009, broken down by five-year age cohorts, nativity, gender, and race/ethnicity for both New England and the nation. We then calculate a 10-year “survival rate” for each group equal to percentage of that group that appears in both the 1990 and 2000 Census. For example, 95% of white males ages 25–29 in New England in 1990 were still living in New England as of 2000. Note that this “survival rate” represents a combination of mortality and migration rates as individuals may disappear over the decade by either dying or leaving the region. These survival rates are applied to the 2009 baseline population to get the projected population for 2019, and again to get the projected population for 2029. As a final step, we calculate labor force participation rates for each group and apply them to our projected populations to get the projected labor force for 2019 and 2029.

Related Posts: A Labor Market Mismatch in New England, Mismatch in the Marketplace: NEPPC Forum to Address Supply and Demand in Labor Force, Too Many College-Educated Workers or Too Few?, The Future of the Skilled Labor Force

[ssba]