“About every two years someone comes up with this story. There is absolutely nothing to it—it’s simply not true,” Peter Capelli, Professor, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, commenting on the Georgetown’s college labor supply shortage forecast.

“About every two years someone comes up with this story. There is absolutely nothing to it—it’s simply not true,” Peter Capelli, Professor, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, commenting on the Georgetown’s college labor supply shortage forecast.

—“Prediction of Worker Shortage Has Critics,” The Press-Enterprise (Riverside, Calif.), April 10, 2010.

The recent response by Anthony Carnevale et al. to our analysis of the fundamental shortcomings associated with their predictions of widespread college labor shortages focuses on three areas. First, they suggest that we are educational Luddites by noting in the title of their response that we believe too many people have earned college degrees in New England. Carnevale et al. claim that we think, “New England is producing 35% more college degrees than are actually required for current and future jobs” because we recognize the real labor market problems that confront too many of our college graduates. We don’t think that New England colleges produce too many graduates, but we do find that a considerable number of recent and past graduates are malemployed and don’t get much of a financial return on their investment and that of society.

We simply argue that Carnevale exaggerates the size of the existing college labor market and overstates demand now – and therefore in the future – because he defines every employed college graduate as being in the college labor market. Why does he do this? Primarily, because he refuses to recognize the widespread problem of malemployment of college graduates, especially in the current, very difficult, employment situation confronting the nation. An even casual reading of numerous articles in the media and on the Internet on the labor market adjustment problems of college graduates, their rising debt loads, and increasing loan defaults would illustrate the situation.

We find that about 25% of all employed college-educated adults in the nation and closer to 40% of recent graduates work in non-college labor market jobs. Some voluntarily do so while others are trapped involuntarily. But, in either case, they receive a substantially diminished rate of return to their degrees compared to those who become employed in a college labor market occupation. We do not argue that these graduates should not have gone to college. Instead, we argue that colleges, employers and other labor market intermediaries need to develop strategies to reduce malemployment rates among college graduates and help them obtain better access to occupations that allow them to utilize their college skills. Otherwise, the expected size of the payoff to a college degree for them is not very high. Denying the existence of widespread and costly malemployment problems does not make this very severe problem go away. It simply diminishes the ability of our education and labor market institutions to effectively respond to the needs of college graduates who are stuck in low-skill, low-mobility and low-wage jobs.

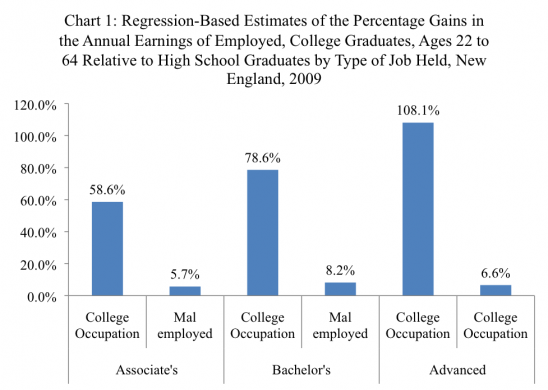

The second issue Carnevale points to is the long-term rise until recently (2000) in the economic return to a college degree, suggesting that we think that college does not pay-off. Again, we have argued that college pays off on average and have written plenty of papers about this. The results of our recent multivariate analysis of the annual earnings premiums of college graduates in New England during 2009 summarized in the Chart 1 below reveal very large earnings payoffs to college graduates. However, the findings clearly reveal that, whether a given graduate’s degree pays off, depends on the success of the individual becoming employed in an occupation that has a substantial set of duties and tasks that utilize the knowledge, skills and abilities that they acquired in college. The estimated annual earnings advantages over and above a high school graduate for those who earn a degree and become employed in the college labor market were 55% for those with an associate degree, 71% for those with a bachelor’s degree, and 107% for those who earned an advanced degree. Among those graduates who were malemployed, however, we found very modest annual earnings advantages ranging from only 5% to 8%.

Source: American Community Survey, Public Use Data Files, analysis by the authors

Carnevale argues that we use a rigid set of “elite, traditional white-collar and professional jobs” to define the college labor market. In fact, we use a very broad-based set of occupations and an objective source of information that utilizes large-scale occupational analysis studies of the knowledge, skills, and abilities used at the workplace. This system was developed and regularly updated by the U.S Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration through its O*NET system. We readily admit that we exclude many occupations from our listing of college labor market jobs, and our argument is that if you include all occupations in the definition of a college labor market (as Carnevale does), then its usefulness as a measure of the demand for college-level skills has lost most of its utility. Including “everything” in your definition is hardly the basis of any classification system that could serve as a meaningful taxonomy of employer requirements around postsecondary knowledge, skills, and abilities.

The findings in Table 1 below provide estimates of the occupational distribution of the jobs held by recent college graduates under 25 who were malemployed during 2009. The table illustrates the kinds of occupations that we exclude when we define the college labor market. The data also illustrate the kinds of occupations Carnevale et al. include when they determine the size of the college labor market. These 15 occupations are dominated by waiter/waitress, bartender, cashier and retail sales jobs, and low-end service and clerical jobs. The inclusion of so many waitress, waiter, and bartender occupations gives a new meaning to STEM occupation. By the Georgetown authors’ reckoning, all of these are part of the college labor market.

Table 1:

Distribution of the Malemployed with a Bachelor’s Degree Only Under Age 25, by Occupation, Annual Averages, 2009, U.S.

| Occupation | Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| Waiters, Waitresses and Bartenders | 10.4 | 10.4 |

| Retail Salespersons | 9.0 | 19.4 |

| Secretaries And Administrative Assistants | 6.4 | 25.8 |

| Customer Service Representatives | 6.2 | 32.0 |

| Cashiers | 4.8 | 36.8 |

| Child Care Workers | 3.6 | 40.2 |

| Office Clerks, General | 3.3 | 43.7 |

| Receptionists And Information Clerks | 2.4 | 46.1 |

| Recreation And Fitness Workers | 2.4 | 48.5 |

| Bank Tellers | 1.9 | 50.4 |

| Miscellaneous Office And Administrative Support Workers | 1.9 | 52.3 |

| Nursing, Psychiatric, And Home Health Aides | 1.8 | 54.1 |

| Food Preparation Workers | 1.7 | 55.8 |

| Stock Clerks And Order Fillers | 1.4 | 57.2 |

| Cooks | 1.3 | 58.5 |

What’s the rationale for including these occupations in the measure of the college labor market? Carnevale et al argue that college degrees generate positive earnings premiums whether graduates are employed as they put it as “insurance agents or a rocket scientist.” But this is a poor example of what they see as our exclusionary classification. We include both of these occupations in our current college labor market definition. We do exclude most clerical, blue-collar production, material moving, retail sales, low-level services and jobs like bartenders such as those listed in Table 1 where entry skill requirements are well below the college level. We suspect that most fair-minded observers would agree that these occupations do not require a bachelor’s degree to become qualified for employment. Nevertheless, the proof is in the pudding and this gets us to Carnevale’s third point.

Carnevale argues that college graduates working in these sorts of non-college labor market occupations earn more than their high school graduate counterparts who are employed in those same occupations—like bartenders or landscapers. As we noted in our initial article in NEJHE, we agree. College graduates who work in occupations outside the college labor market do typically earn slightly more than their high school graduate counterpart, but not much more, and a lot less than their fellow college graduates who did become employed in a college labor market job.

Our findings clearly reveal that in New England college graduates at the associate, bachelors and advanced degree levels employed in occupations outside of the college labor market had annual earnings that were only 5% to 8% higher than those of their high school graduate counterparts, a small but statistically significant annual earnings advantage. Based on other recent research by the Center for Labor Market Studies, we find that some of this advantage is associated with better literacy and/or numeracy skills, making these malemployed college graduates slightly more productive than their high school graduate counterparts—within the constraints of the task/skill requirements of their occupations. That is, being better at math may raise the earnings of malemployed college graduates relative to employed high school graduates—but not by much.

A malemployed college graduate’s earnings are constrained because their ability to use the college-level skills they acquired are limited by the job duties and work tasks associated with their occupation. Graduates of a rocket science program who work as bartenders gets bartender pay. However, their pay will rise sharply when they become employed in a rocket scientist occupation where they are able to engage in a set of job duties and work tasks that better capitalize on the knowledge, skills and abilities that they developed while earning their degree.

What is the evidence for this? As our regression results reveal, college graduates in New England who work in college labor market occupations had annual earnings premiums during 2009 that were about 10 times greater than those of their counterparts who worked in non-college labor market jobs. New England residents with associate degrees who worked in college labor market jobs had an annual earnings premium of 58% compared with just 5% premium for their graduate peers who worked in non-college labor market occupations. At the bachelor’s degree level, New Englanders who work in the college labor market had an annual earning premium of 78% compared to only 8% among those who were employed in jobs outside the college labor market. At the advanced degree level, those employed in the college labor market had an annual earnings advantage of 108%, compared with just 8% for those who worked outside the college labor market

Carnevale and his colleagues do a disservice to the nation’s higher education system by so dramatically overstating the size of the college labor market. The Georgetown projections exaggerate the demand for college degrees in the present and future while at the same time ignoring the large and severe problems of malemployment and even joblessness among college grads around the nation. The consequence is that it suggests that colleges should prepare for a labor shortage problem that is based on a false premise. The nation’s labor markets continue to struggle with unemployment rates that hover close to 10% and under-utilization rates closer to 20%. The Georgetown analysis also fails to recognize the collateral impact of malemployment among college graduates. As college grads move down the labor market queue into occupations dominated by those with less schooling, the employment rates among those with fewer years of schooling plunge. Added labor supply also depresses their wages. Especially hard hit are non-college-educated teens and young adults who can no longer find work as recent college grads crowd them out of the labor market. These displacement effects further erode the value of a college education. So the problem of malemployment among college grads creates additional problems of unemployment and underemployment among non college grads, especially teens and young adults.

The substantial earnings losses associated with malemployment of college graduates also reduce their tax contributions to federal, state and local governments in the form of lower income taxes, Social Security payroll taxes, and state sales taxes. Malemployed graduates are also much less likely to receive health insurance and pension coverage from their employers, further reducing the private and social return to their investments in college.

It is time to stop fantasizing about the future and to start addressing the severe malemployment and joblessness problems confronting college graduates in the present day. The nation needs a laser focus on creating college-related employment opportunities and upward mobility pathways in today’s job market. Right now, there are at least five unemployed workers for every vacant job, and our recent analysis of state job vacancy data suggests that the ratio is 8 to 1 when we focus on only full-time job vacancies and unemployed persons. The pace of new job creation in the U.S. has been sluggish at best. Indeed, at the current rate of growth, the nation won’t recover the entire payroll jobs lost during the Great Recession and its aftermath until the end of 2017. If the labor force continues to grow as projected, the pace of reduction in unemployment rates will be even slower. Higher education’s major challenge is not a labor shortage in 2018. Instead our task is helping our graduates find intellectually fulfilling and economically remunerative employment that provides upward mobility, and favorable economic returns on skills and abilities that all of us desired when we entered college.

Paul E. Harrington is associate director of the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University. Andrew M. Sum is the center’s director.

[ssba]