Demographic changes, shrinking federal and state support, a lethargic economic recovery, anemic endowment returns and increasing wariness of student loan debt comprise a perfect storm converging on America’s mid-sized colleges and universities, threatening to swamp their finances in seas of red ink.

Faced with an urgent need to address cost structures, these institutions are scrambling to adapt educational offerings to compete in this changing environment. They would do well to take a lesson from their better-heeled brethren when it comes to addressing an important, but often overlooked, area of fixed cost structures: risk management.

For most mid-sized and smaller institutions of learning, risk management has historically followed a rather straightforward formula: buy insurance. Simple, right? From property and casualty to professional liability, employee benefits, sports and travel, typical exposures are addressed as a cost of doing business. For larger institutions, however, the approach to risk management and control is anything but typical.

Faced with operational complexities on par with those of a city, larger colleges and universities have long understood the value of taking a more strategic approach to understanding and managing enterprise risks. Personnel dedicated to risk analysis and control at these institutions are tasked with taking a holistic view of the exposures, liabilities and responsibilities, as well as developing innovative ways to reduce the cost of dealing with them.

You might think about it as the relative difference between a married couple with a child doing their own taxes and General Electric maintaining a well-staffed department of experts handling theirs.

The payoff for this extensive, dedicated effort is actually two-fold: a smarter, more cost-effective approach to managing the structural operational cost (risk), as well as better insight into and control over a number of key aspects of their operations.

But can mid-sized and smaller institutions afford this approach? Not the exact approach perhaps, but a subset of this approach could make a real difference.

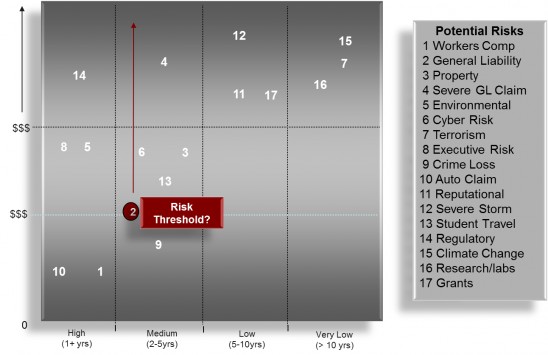

One particularly useful method proven successful in helping higher ed institutions adopt a more strategic mindset in identifying and managing their risk and ultimately reducing costs is the development of an enterprise risk map (see Sample Risk Map below).

A risk map is a way of visualizing the various types of potential losses an institution faces across its entirety of operations, the likelihood each loss has of occurring and the likely financial impact. Each data point is categorized and appropriately placed in various quadrants on the risk map. The objective is to identify the top risks facing the institution by using the so-called “critical needs assessment approach,” which looks at the likelihood of losses and their potential severity.

In larger higher ed institutions with dedicated functions, the process of building a risk map typically starts with the risk manager assembling an in-house team to perform a “Campus Exposure Analysis.” For mid-tier and smaller schools, this could be headed up by a chief financial officer or other higher-level business administrator.

The team itself comprises key operations stakeholders such as finance, facilities, campus police and security, environmental health & safety, faculty and administration. Each is responsible for bringing forward a delineation of current practices, operations and procedures so they can be examined from a loss and liability perspective, and then quantified in terms of potential impact and likelihood to occur. This exercise requires a close review of insurance requirements and major contracts as a way of surfacing loss and liability potentials and relevant data. Some examples include:

- Construction/renovation. These projects, large and small in scope, are a regular feature of campus activity. Are the contractors hired assuming the associated costs of liability protection?

- Vendors. From food services to janitorial staff, vendor presence has expanded over the decades and their work can convey far-reaching exposures (ranging from e-coli and norovirus to slip and falls) that should not necessarily be backstopped by an institution’s policies.

- Consulting and professional services. Acting on advice can carry consequences. Initiatives on any number of topical fronts (sexual assault prevention, perhaps) can create a pathway for exposure.

- All major leases. Traditionally understood as exposures incurred in the use of leased equipment, many institutions are opening new realms of possible liability as they lease space to incubators, startups and spinoffs.

- Special events. From TEDx talks to hip hop concerts, the same facility can host many different types of events, each with very different possible liabilities. Should the institution, event organizer or performing act provide the indemnity?

- Hold harmless and indemnification agreements. Do current policies, contracts and agreements, where possible, include language that offloads risk liability from the institution?

- Independent contractor. Similar to a vendor but closer to an employee, rules are changing as the so-called gig economy blurs lines. Is agreement language up to date with changes in law?

A detailed, line-by-line comprehensive review of all losses experienced by the institution is conducted to build out real-world historical data, and this information, in turn, informs the placement of risk points within the map’s quadrants.

Once the risk map development team has gathered its information, plotted the results by quadrant and agreed on the accuracy of its representation, a designated member of the group will typically take the graphic and back-up documentation to the “C-Suite” of institutional administration—chief legal counsel, president, etc.—to drive a comprehensive, better-informed process of aligning the costs of effective risk control with actual loss potential and school initiatives and priorities. It’s a visual communication that illustrates the full scope of risks faced and promotes a far more vigorous decision-making process.

The visual nature of the risk map is particularly useful in that it combines subjective judgments with data, and makes this insight accessible for evaluation and discussion by both novice and expert, alike. Examples of possible outcomes are:

- Data-driven identification of the top risk facing the school, understanding high-frequency, low-cost events like slip and fall claims where the cost is straightforward and easily managed versus an emerging, multifaceted issue such as sexual assault claims, where monetary cost is only one aspect of damage.

- Re-evaluation of current risk management practices, operations and procedures. Identification of areas—from redrafting language for leasing agreements and contract employees to suicide awareness training for staff—where changes can improve outcomes, including risk costs.

- Alignment of risk management activities with university objectives. Addressing certain areas identified as liability risks, like sexual assault allegations, can also contribute materially in advancing overall objectives, such as improving institutional reputation and enrollment goals.

- Agreement on future risk management actions that limit loss exposures, reducing costs.

Once established, future iterations of the map can be more easily created and then adapted to incorporate new functions and variables. There’s always a new storm on the horizon. A strategic risk management approach will pay dividends for schools seeking safe passage on the road ahead.

Jane Dickerson is senior vice president and higher education practice leader of Risk Strategies Company. She also chairs the Affiliated Committee of the University Risk Management and Insurance Association, an international nonprofit educational association focused on advancing the discipline of risk management in higher education.

____________________________________________________________

Sample Risk Map…

A risk map plots potential liabilities and exposures (numbered list on right) against their possible financial impact (vertical axis) and their likelihood of occurrence over time (the horizontal axis). In the above example, Auto Claims (10) map as a high frequency, but relatively low cost risk; whereas a terrorism incident (7) is mapped as a low likelihood event with potentially catastrophic impacts.

____________________________________________________________

Related Posts:

NEBHE’s Higher Education Innovation Challenge

[ssba]